Saturday, November 11, 2006

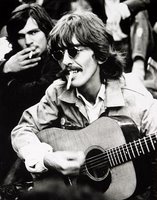

Interview: George Harrison, London - March 11, 1970

Date: 11 March 1970

Time: 5:00 - 6:00 pm

Location: Studio H25, Aeolian Hall, London

Interviewer: Johnny Moran

Broadcast: 30 March 1970, 4:31-5:15 pm

BBC Radio 1

The Beatles Today

GEORGE: Ringo's completed a great album. I think it's called . . . Sentimental Journey it's called. And it's all the songs that Elsie and Harry and his uncle and aunties, that's his father and mother, they used to all sing and have parties all the time. So he sings all these old songs with the sort of old arrangements. He doesn't do the sort of modern arrangement, and it's really a nice album. Then John's doing an album, a Plastic Ono album, I think he's going to do that with Phil Spector. And I think Paul's doing an album which is, I should imagine like, if you remember Eddie Cochran did a couple of tracks like "C'mon Everybody" where he played bass, drums, guitar, and sang. So Paul's doing this sort of thing, where he's going to play all the instruments himself. Which is nice, because he couldn't possibly do that in the Beatles, you know, if it was a Beatle album automatically Paul gets stuck on bass, Ringo gets on drums. So in a way it's a great relief for us all to be able to work separately at the same time, and so maybe if I get a chance, I'd like to do an album as well, just to get rid of a lot of songs. So maybe. . .

JOHNNY MORAN: Just a George album.

GEORGE: A George album, [laughs] and so I'll try and get that together sometime during this summer, and I expect by that time we should be ready to do a new Beatle album.

---

GEORGE: It's the end of the Beatles like maybe how people imagine the Beatles. The Beatles have never really been what people thought they were, anyway. So, in a way, it's the end of the Beatles like that, but it's not really the end of the Beatles. The Beatles, you know, are going to go on until they die.

---

GEORGE: As far as the Beatles go we've got the Let It Be album. It's being held up really because we're trying to put the film out in about forty different cities throughout the world all at once, rather than sort of put on a premiere in New York and then let the critics say, "oh, well we think it's this, and we think it's that."

JOHNNY MORAN: What's the Beatle film going to be about?

GEORGE: The Beatle film is just pure documentary of us slogging and working.

JOHNNY MORAN: On Let It Be?

GEORGE: Yeah on the album, and the hold-up of the album is because we want this film to go out simultaneously. Originally we were rehearsing, we were rehearsing the songs that we were planning to do in some big TV spectacular or something. We had a vague idea of doing a TV show, but we really didn't know the formula of how to do it because we didn't really want to do . . . obviously we didn't want to do a Magical Mystery Tour, having already been on that trip, and we didn't want to do sort of the Tom Jones spectacular. And we're always trying to be . . . to do something slightly different. And we were down in Apple rehearsing, and we decided to film it on 16mm, to maybe use as a documentary, and the record happened to be the rehearsal of the record, and the film happened to be, rather than a TV show, it happened to be the film of us making the record. So it's very rough in a way, you know, it's nice because again you can see our warts. You can hear us talking, you can hear us playing out of tune, and you can hear us coughing and all those things. It's the complete opposite to this sort of clinical approach that we've normally had, you know, studio recording, everything, the balance, everything is just right, and you know, the silence in between each track. This is really not like that, but there's nice songs, really good songs on it. "Let It Be", of course, and "Don't Let Me Down." I think they're the two that you people would have heard of. There's one song which is a 12-bar, because I've never written a 12-bar before, and that's called "For You Blue." And it's just a very simple, foot-tapping 12-bar. The other one is a very strange song which I wrote the night before it was in the film, you see. At this time we were at Twickenham, and I wrote this song, it took five minutes just from an idea I had. I went into the studio and sang it to Ringo, and they happened to film it. And that film sequence was quite nice, you see, so they wanted to keep that sequence in the film, but I hadn't really recorded it in Apple with the rest of the songs. So we had to go in the studio and re-record it. Also, we put on "Across The Universe," which was a song on the album . . . for the charity album, it came out for Wild Life and that really got lost. It's been around for about three years now, 1967 [sic] I think we did that.

---

GEORGE: In fact, some people may be put off at hearing it, it sounds maybe . . . my attitude when we decided to use it as an album was that people may think we're not trying, you know, because it's really like a demo record. But, on the other hand, it's worth so much more than those other records because you can actually get to know us a bit, you know, it's a bit more human than the average studio recording.

---

GEORGE: I certainly, you know, don't want to see the end of the Beatles. And I know I'll do anything, you know, whatever Paul, John, Ringo would like to do, you know, I'll do it.

Friday, September 22, 2006

George Harrison's California Trip

by Neil Aspinall

by Neil AspinallTUESDAY AUGUST 1 - Today we flew from London to Los Angeles by polarflight jet. We were George and Pattie, our electronic genius-type mate called Magic Alex and yours truly. The Harrisons travelled as "Mr. and Mrs. Weiss" -- which happened to be the name of the man who was going to meet us and look after us in California. I mean Nat Weiss, who manages The Cyrkle and directs the corporation known as Nemperor Artists in New York. First problem on arrival was the lack of one vital Aspinall suitcase, left 6,000 miles behind us in London. You gain time when you fly from Britain to America. We'd set off at lunchtime but it was only early afternoon in Los Angeles when we drove from the airport to the private house we had rented for the week.

HILL HOUSE

It was a smallish, very beautiful, compact place with a little, round swimming pool up in the hills of Hollywood in a street called Blue Jay Way. Don't they have picturesque names? The house belonged to a lawyer who was vacationing in Hawaii. The long flight had left everybody a bit tired but Pattie stayed up long enough to call her sister, Jenny, who was staying in San Francisco just up the West Coast a bit, and she said she'd fly down to join us. And George phoned our good friend Derek Taylor who started writing down the complicated instructions for getting from his place to ours.

NEW SONG

The Telephone conversation with Derek provided George with the inspiration to write a song called "Blue Jay Way", he sat there working it out on a mini-organ while he waited for Derek. You'll be hearing "Blue Jay Way" in the "Magical Mystery Tour" TV show if not before.

Wednesday August 2 - Slept late, then I did a bit of shopping, then we all went over to Ravi Shankar's Music School. Sat and watched Ravi teaching this huge class of about 50 people--very mixed crowd with people between the ages of about 16 and 30, all keen students of Indian music. Ravi's tabla drummer Alla Rahka gave a lesson which we watched for a bit before going out with Ravi to have a meal on Sunset Strip.

Thursday August 3 - Early in the morning--well, about eleven you know--George went over to the School with Alex and myself while Pattie and Jenny went sightseeing. Tomorrow night Ravi has his concert at the Hollywood Bowl so this morning he gave a press conference. All the local radio and press people knew George was about and, of course, they swooped on him with all sorts of questions ("What do you think of LSD?"..."Where are you staying, George?") during the conference. In the afternoon George and I went to a shop called Sidereal Time. There and elsewhere we picked up a load of shirts and things plus some moccasin-type boots and groovy posters. In the evening we heard Ravi give a lecture on the history of Indian music and then went over to a Mamas and Papas recording session with Derek Taylor.

NEW GUITAR

One of the session men there had this fantastic new guitar--a first prototype and something quite special. I daren't tell you what's so special about it because I've just arranged to have a couple of them made (one will be a bass guitar version) for the Beatles and it's all supposed to be very secret! Anyway it was now the middle of the night but George couldn't resist having a go on this sshh-you-don't know-what guitar.

Friday August 4 - Tonight at nine o'clock Ravi's 4-hour concert began at the Bowl. With him were a lot of his finest students, a marvellous night of music. First we watched Bismillah Khan and party with Bismillah playing an Indian flute called a shehnai. Whatever he played the rest of the party--students--would try to follow until his music got so advanced that they had to leave it to him! Then came a South Indian drummer playing an instrument known as a mridangam, a sort of old classical drum, which you bang at both ends. Then came Ali Akbar Khan and his son Ashish playing modern little drums they call sarods, each almost "talking" to the other via his drum. Finally, before Ravi himself, came the tabla player and teacher Alla Rahka, Ravi's own drummer, who stayed on stage to accompany Ravi's sitar for the final hour of the programme. I hope I've got all my spellings O.K.--I checked them all over with George when I was writing up this diary, but don't blame him if there are any mistakes because my own handwriting isn't that easy to read back!

Saturday August 5 - This morning we all went along to some recording studios opposite Ravi's school to watch Alla Rahka and a South Indian drummer recording a duet to fill one whole side of an LP disc. A South Indian singer--using his voice just like an instrument--is doing the whole of the second side of the LP. Which reminds me that George has been very pleased to accept an invitaiton to write the sleeve notes for another Indian LP which is being recorded here this week. By Ali Akbar Khans' son Ashish. Later in the day we saw Derek, his wife and his great bunch of kids. Went with them all to the downtown area of Los Angeles to visit Alvera Street, a very historic place. It's been preserved as a tourist attraction--complete with some of California's very earliest brick-built houses. Bands were playing and there were lots of little stalls selling souvenirs made in Hong Kong! We had a Mexican meal in one of the funny little restaurants in Alvera Street and bought a batch of wonderful Mexican pictures, paintings done on velvet. Mine shows a mournful old clown with a battered old hat holding a big flower and pulling the petals off one by one! They were very cheap--just a few dollars each--and yet very large. We also bought a matador one with a big green bull on it. George left Alex and myself buying colourful waistcoasts while he trotted over to Ravi's place to collect a sitar he was buying.

Sunday August 7 - George went off early on his own to see Ashish and talk about the LP sleeve notes and everything. So later on when the rest of us set off for Disneyland, George stayed behind. We didn't stay at Disneyland all that long but it's a fantastic place. We visited "Tomorrowland", "Fantasyland" and a bit of "Frontierland". I got into this telephone booth where you can phone up all the famous Disney cartoon characters. I phoned Pluto but a voice said "Sorry he's busy. This is Goofy,"!! In the evening we all went over to Ravi's house.

Monday August 8 - Today we went up to San Francisco and walked around Haight-Ashbury. Derek came with us. It got a bit bad after a time. There was this ridiculous procession of people following George as if he was the New Pied Piper. But he didn't lead them to the river. Anyway it was a good day, a good scene to see with things we were glad about and things we were sorry about (such as those beggars sitting in the street conning money out of tourists) and it was the first time we'd really looked at San Francisco as a place although we'd been before for Beatles concerts.

Tuesday August 9 - Packing and getting ready for tonight's flight home. Four little fans called at the house but they were O.K. and there wasn't any trouble and George enjoyed seeing them. Oh yes, I forgot to tell you--my case DID arrive from London so I HAVEN'T been wandering round for the last 8 days in the same sticky clothing!!!!

Visit California Today: Book flight + hotel together and save!

Magic Alex – A World of Inventions

Not that I found it much easier dealing with the likes of Magic Alex and the Fool. No matter how much money the Beatles allocated to Apple Electronics, Alex would invariably complain that it wasn’t nearly enough to cover the cost of his fantastic inventions. At this particular juncture, he claimed to be hard at work creating an artificial sun that would materialize over Baker Street to light up the sky on the boutique’s opening night. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 150)

Some of his other ideas seemed fantastical – an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations which would screen the Beatles from their fans and an artificial sun which would illuminate the night sky by laser beams. (The Beatles Encyclopedia, p. 717)

Among the amazing devices he offered John was a car paint that would change color at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans, an electrostatic wallpaper that would make any room into a total sound chamber, and an artificial sun that would illuminate the night sky by means of laser beams. (The Lives Of John Lennon, p. 244)

For John he was full of ideas for magic inventions, incredible things he had figured out how to make: air colored with light, artificial laser suns that would hang in the night sky, a force field that would keep fans away, and wallpaper that was actually a paper-thin stereo speaker. (The Love You Make, p. 206)

Magic Alex was commissioned to design the store’s lighting, and he spoke of hanging a sun in the street to light up the night sky for the opening. (The Love You Make, p. 255)

In the meantime, Magic Alex had received a large sum of money to work on an artificial sun which was going to hover over Baker Street and light up the sky during the boutique’s gala opening. Needless to say, at 8.16 p.m. on Monday, 4 December 1967 (the time John Lennon had decreed for guests to arrive for the grand opening), there was no sign of the artificial sun. (Many Years From Now, p. 446)

Alex had hung no magic lighting in the street; it had proved too complicated, and the lighting in the store was expensive but not very unusual. (The Love You Make, p. 256)

Also conspicuous in its absence was the artificial sun with which Magic Alex had promised to illuminate Baker Street for our gala opening. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 153)

Despite the lack of the promised artificial sun at the Apple boutique opening, Magic Alex had managed to remain in favour. (Many Years From Now, p. 531)

Anti-Gravity Machine

Other miraculous gadgets – domestic force fields, anti-gravity machines, and flying saucers – would follow, he assured the millionaire Beatle, as soon as he obtained the financial backing necessary to turn them into a reality. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 119)

Coloured Air

For John he was full of ideas for magic inventions, incredible things he had figured out how to make: air colored with light, artificial laser suns that would hang in the night sky, a force field that would keep fans away, and wallpaper that was actually a paper-thin stereo speaker. (The Love You Make, p. 206)

Device Preventing Records From Being Taped

“He had an idea to stop people taping our records off the radio – you’d have to have a decoder to get the signal. And then we thought we could sell the time and put commercials on instead. We brought EMI and Capitol in from America to look at it, but they weren’t interested at all.” – Ringo Starr (The Beatles Anthology, p. 290)

Conversation on the set of Let It Be, 10 January 1969:

Michael: Is that device he’s going to put on records going to work?

George: Yep.

Michael: Where you can’t tape it? Great idea.

Ringo: If it gets put on.

Michael: But surely, I mean, it’s in the interests of all the people who put out records to have it on.

Ringo: Yeah, but it’s…

Michael: Not in the interest of people who make tape machines.

Ringo: I mean, I, I think it should be on, but John thought it was ‘bad Beatles’. Stopping all the kids taping it.

George: Yeah, but the thing is the Beatles now, in America they have, you know, those cassette tapes. Well that means that uh, it’s easy. Somebody just gets, buys one, even. And then rolls off their own few million and sell it. And there’s, you know, everybody loses out on that, because people who bought it, and yet some cunt’s made all the money, for doing fuck all except thieving it.

Ringo: Did you hear it about, you know, the signal that they’re putting on, you could put adverts on it.

Michael: Yes, well the one Neil talked about is ‘this is Apple Records’.

George: Messages or talking anything, you know, like…

Michael: Yes, ‘please … please come home, all is forgiven’. It’s a great idea, I think. Because basically, if you’re rich enough to have a tape recorder, you’re rich enough to buy a record, really.

Domestic Force Field

Other miraculous gadgets – domestic force fields, anti-gravity machines, and flying saucers – would follow, he assured the millionaire Beatle, as soon as he obtained the financial backing necessary to turn them into a reality. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 119)

A force field that would surround a building with coloured air so that no one could see in. A force field of compressed air that would stop anyone rear-ending your car. (Many Years From Now, p. 375)

Among the amazing devices he offered John was a car paint that would change color at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans, an electrostatic wallpaper that would make any room into a total sound chamber, and an artificial sun that would illuminate the night sky by means of laser beams. (The Lives Of John Lennon, p. 244)

Mardas promised miracles. Abbey Road had eight-track facilities. Apple would have 72. And away with those awkward studio “baffles” around Ringo and his drum kit! (Placed there to prevent leakage of the drum sound onto the other studio microphones.) Magic Alex would install an invisible sonic beam, like a force field, which would do the work unobtrusively. (The Beatles Recording Sessions, p. 164)

I suppose his prize idea was his sonic screen. I was informed of this work of inventive genius by the boys one day. ‘Why do you have to put Ringo with his drums behind all these terrible screens?’ they asked, ‘We can’t see him. We know it makes a good drum sound, and it cuts out all the spill on to our guitars and things, but damn it, with those bloody great screens locking him in, it makes him feel claustrophobic.’

I waited silently, knowing that the problem would have been solved by a flash of Greek inspiration. And so it had.

‘Alex has got a brilliant idea! He’s come up with something really great: a sonic screen! He’s going to place these ultra-high-frequency beams round Ringo, and when they’re switched on he won’t be able to hear anything, because the beams will form a wall of silence.’

Words, I fully admit, failed me.

The trouble was that Alex was always coming to the studios to see what we were doing and to learn from it, while at the same time saying ‘These people are so out of date.’ But I found it very difficult to chuck him out, because the boys liked him so much. Since it was very obvious that I didn’t, a minor schism developed. (All You Need Is Ears, p. 173)

For John he was full of ideas for magic inventions, incredible things he had figured out how to make: air colored with light, artificial laser suns that would hang in the night sky, a force field that would keep fans away, and wallpaper that was actually a paper-thin stereo speaker. (The Love You Make, p. 206)

The Beatles were impressed by some electronic gadgetry he made for them and were intrigued by the various inventions he said he could devise, including an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations and a paint which glowed when connected to an electrical current. (The Encyclopedia Of Beatles People, p. 217)

Electric Spoon

Such talent shouldn’t go to waste, I thought. Why not ask Alex to solve a small domestic problem for Lesley and me? When I was out in our kitchen telling Lesley about Alex’s space-age speakers, she was making some sauce.

‘This sauce is bringing me down,’ she said. ‘I have to keep stirring it all the time. If I want to go across the kitchen to do anything else, I have to wait, because the sauce will go wrong if I don’t keep stirring it. Why doesn’t Alex make some gadget that will stir a sauce on its own and let me get on with the other jobs? It’d sell a million!’

I think Lesley was just joking, but I decided to put Alex to the test. I put the problem to him and he went very quiet.

‘I will think about it.’

Three weeks later, Alex phoned me at the office and asked me to come to the workshop. He had a gas ring there with a pan of water simmering on it.

‘Now, you look at this.’

Alex took a roughly-soldered metal disc about half a inch thick and two or three inches in diameter.

‘Now watch.’

He popped the disc into the water. There were no wires, no attachments of any kind and nothing inside the disc, but the peculiar object started going round and round and up and down in just the way needed to stir the water!

‘There is your electric spoon.’

I wanted to take it away and show it to Lesley, but he wouldn’t let me have it. Too roughly made, he said. I should wait until it was properly finished.

The man’s mind spins out ideas like a Catherine Wheel spins out sparks. George wants him to install a voice-sensitive lock on his door so that his friends’ voices can be programmed into it and they can just walk up the door and say, ‘Hello, it’s me,’ and the door will open for them. Anyone else would have to knock! Alex has designed a tiny throwaway radio supposed to sell for a few pence and made out of a few pieces of plastic. I heard a prototype that would fit in your pocket and looked as if it were made out of the leftovers from a child’s construction kit, but it worked just fine. Quite an inventor! (Yesterday: The Beatles Remembered, p. 147-148)

Floating House and/or Recording Studio

We flew out a second time with Magic Alex. He was talking about building a bubble-house that floated in mid-air above the island! Utterly crazy. It would have been blown half over Ireland in those winds. Alex is still figuring out designs for avant-garde houses. What a joke. (Yesterday: The Beatles Remembered, p. 190)

After that first trip, the people of Westport were in no doubt as to who the real purchaser of the island was and the second time we went we got quite a reception. John’s friend ‘Magic’ Alex Mardas was involved by this time, with his plan to build John a house on Dorinish and a ‘recording studio which floats a foot off the ground so there are no vibrations.’ (A Secret History, p. 163)

A house that would hover in the air, suspended on an invisible beam like something out of a Flash Gordon movie – which may well have been where he got the idea. (Many Years From Now, p. 375-376)

Flying Saucer

“Oh well, Pete,” said John. “We might as well go in anyway. There’s an amazing Greek fellow upstairs I really want you to meet. His name’s Alex, and he’s magic.”

Abandoning his purple, green, red, and yellow paints, John ushered me into a seldom-used study, where we found a slight, fair-haired figure squatting on the floor, intently poring over some blueprints. “He’s inventing a flying saucer,” John explained. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 118)

Other miraculous gadgets – domestic force fields, anti-gravity machines, and flying saucers – would follow, he assured the millionaire Beatle, as soon as he obtained the financial backing necessary to turn them into a reality. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 119)

“And that’s another thing: I was going to give him the V12 engine out of my Ferrari Berlinetta and John was going to give him his, and Alex reckoned that with those two engines he could make a flying saucer.” – George Harrison (The Beatles Anthology, p. 291)

Despite the lack of the promised artificial sun at the Apple boutique opening, Magic Alex had managed to remain in favour. His next projects were to be a flying saucer and magic paint that would render objects invisible: clearly both highly marketable inventions. This time his Boston Place workshop suffered a mysterious fire just before he unveiled his masterworks. It would obviously take months before he could produce new working prototypes so he bought himself another stay of execution. (Many Years From Now, p. 531-532)

“What Magic Alex did was pick up on the latest inventions, show them to us and we’d think he’d invented them. We were naïve to the teeth … I was going to give him the V12 engine out of my Ferrari Berlinetta and John was going to give him his, and Alex reckoned that with those two V12 engines he could make a flying saucer. But we’d have given them to him – ‘Go on, go for it!’ – daft buggers.” – George Harrison (I Me Mine, via Many Years From Now, p. 376)

We also set Alex up with his own laboratory in a Boston Street warehouse, where he claimed to be putting the final touches on – among other things – his flying saucer and a new kind of paint that would render objects invisible. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 159)

“Loudpaper”

Paul: ‘He would sit and tell us of how it would be possible to have wallpapers which were speakers, so you would wallpaper your room with some sort of substance and then it could be plugged into and the whole wall would vibrate and work as a loudspeaker – “loudpaper”. And we said, “Well, if you could do that, we’d like one.” It was always “We’d like one.”’ (Many Years From Now, p. 376)

For John he was full of ideas for magic inventions, incredible things he had figured out how to make: air colored with light, artificial laser suns that would hang in the night sky, a force field that would keep fans away, and wallpaper that was actually a paper-thin stereo speaker. (The Love You Make, p. 206)

“He thought of using wallpaper which would act as loudspeakers: you would paper your room with speakers. There is a lot of technology coming in now, but I don’t think it existed then. It was just talked about in scientific journals that we didn’t read, but Alex did. He was a nice bloke and we got on.

“Alex became our man for Apple Electronics, because we thought if he could make loudspeakers out of wallpaper it would be great. But he never came up with it. He had a little laboratory and he did one or two fun things, but it didn’t end up as he’d said it would. He’s around still. He uses his proper name now.” – Paul McCartney (The Beatles Anthology, p. 290)

Among the amazing devices he offered John was a car paint that would change color at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans, an electrostatic wallpaper that would make any room into a total sound chamber, and an artificial sun that would illuminate the night sky by means of laser beams. (The Lives Of John Lennon, p. 244)

“As I say, this was John’s doing. This was John’s guru, but we were all fascinated by the talk, which was rather sci-fi but the idea being that you could do it now. In the sixties there was this feeling of being modern, so much so that I feel like the sixties is about to happen. It feels like a period in the future to me, rather than a period in the past.

“I was just going along with the thing. We committed ourselves with Apple Electronics to make the little gadgets of tomorrow: the wallpaper loudspeaker, the phone that would respond to voice commands. We were thinking this could happen in five years, whereas it’s taken a little longer. A lot of it is still not online but I think it’s accepted that it will be, so we weren’t being stupid, but we were probably overreaching. We were thinking, if he’s got a little place, he may be able to come up with something. Then we’d involve some big electronics giant and say, ‘Come on, Grundig, we’ve patented this. Surely you’ll want this? You could make it great.’ We were on to all those sort of schemes but I don’t think it was so much to make money as to move things ahead. So the scientific ideas would be available.

“We were doing the wallpaper speakers so we could have them! Then I think it just ran on. Our friends would want them too, so that’d be a few more, and then, why not let everyone have them? I’m trying to remember why we even bothered getting involved now. Hopefully for all the right reasons. So we were committed to this electronics company which we registered and he was in some back room trying to develop something. I’m not sure what. I was a bit suspicious. ‘Well, what’s he got then? What is it we’re working on? Is it the loudpaper?’ I always sensed that there wasn’t going to be a product there, and it was a bit of a wild-goose chase and we’d move on from that to the next thing.” – Paul McCartney (Many Years From Now, p. 442-443)

Another time I came into Alex’s workshop to find it full of beautiful music being played on what appeared to be a very high-quality system. The tape deck was playing and the amplifier was on, but I could see no sign of any loudspeakers.

‘That’s groovy music, Alex, but where are your speakers?’

Alex pointed to a couple of polystyrene ceiling tiles, each about a quarter of an inch thick. ‘There they are.’

On each tile there was a blob of what looked like glue, and a spiral of the same material leading out to the edge. Set into the centre blob was the finest imaginable copper wire. Could this piece of household junk be producing such wonderful music?

‘Come on, Alex. You’re kidding me. Where have you hidden the real speakers?’

‘I am not kidding. You pull out the wire and the sound will stop. It does not matter. I stick it back in.’

I gently pulled out the wire from one of the tiles and one channel of the stereo disappeared!

‘That’s incredible!’

Alex hadn’t finished yet. ‘I have this idea,’ he went on, ‘that we sell rolls of wallpaper with these speakers set in it. That way you have speakers all round your room, whatever height you want. Good, no?’

Amazing! To produce sound of the quality I heard from an ordinary speaker would have needed a cabinet the size of a refrigerator! (Yesterday: The Beatles Rememberd, p. 146-148)

Metal Hot/Cold Device

“One invention he had was amazing, though. It was a small square of metal, like stainless steel, with two wires coming out of it to a flashlight battery. If you held the metal and connected the wires one way, it would very quickly become so hot you had to drop it. Then, if you reversed the wires, it got as cold as ice.” – George Harrison (The Beatles Anthology, p. 290)

Nothing Box

Alex’s first project was a box filled with flashing lights, covered in a transparent membrane. They called it a “psychedelic light box” – a brand-new idea at the time – and sold it to the Rolling Stones, who immediately added it to their act. (The Love You Make, p. 205)

One day, when Alex brought John a plastic box filled with Christmas tree lights that did nothing but blink on and off randomly until the battery ran down and the thing blinked itself to death, John was thrilled. It was the best gift an LSD freak could want. In thanks, John elevated him to the royal circle as the Beatles’ court sorcerer and dubbed him “Magic Alex.” (The Love You Make, p. 206)

Alex didn’t need to convince the Beatles that his gadgets had some practical value. He brought them an electric apple which pulsated light and music and a “nothing-box” which had twelve lights, ran for five years, and, as its name suggests, did exactly nothing. The Beatles were mightily impressed and turned out their wallets. None of the devices produced by Alex for Apple ever reached the marketplace. The patents lie in a drawer at the London office, waiting for Allen Klein to decide what to do with them.

The funding of Alex only accelerated the tremendous spending of Beatle money already underway. (Apple To The Core, p. 87)

Often he [John Lennon] would stare at the blinking “nothing box” Alex had presented to him or at the walls and shadows until the drugs wore off. (The Love You Make, p. 211)

Magic Alex, in turn, bestowed on John an assortment of original novelties, such as the “nothing box” that John liked to stare at for hours on end, trying to predict which of the flashing red lights would wink on next. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 119)

Alexis Mardas was an inventor of electronic gadgets. He invented the “nothing box” at which John would gaze for hours, trying to guess which of the series of red lights would flash on next. (Shout!, p. 316)

One night, several weekends after my first encounter with Alex, John and I were sitting up together when it suddenly occurred to him that the following day was the Greek’s birthday. Though John rarely went out of his way to acknowledge such occasions, his esteem for Alex was such that this particular birthday proved the exception to the rule. “Fuck me,” he said. “Magic Alex is coming round tomorrow, and I haven’t even got anything for him. What can I give him, Pete?”

“I dunno,” I said. “What sort of thing does he like?”

“Well,” said John, after a moment’s thought. “He did quite fancy the Iso Griffo.” This was in reference to the magnificent Italian sports car for which John had recently paid a small fortune at the Earl’s Court Motor Show. At the time, in fact, John’s was the only Iso Griffo in all of Britain. “Let’s give him the fucking Iso, then!” he exclaimed.

Without further delay, John retrieved several spools of ribbon, and beckoned me out to the driveway, where we tied the ribbons all around the Iso and crowned its roof with an enormous bow. “There’s your birthday present,” John announced casually, when Alex arrived the next morning. The birthday boy, needless to say, was suitably impressed.

Magic Alex, in turn, bestowed on John an assortment of original novelties, such as the “nothing box” that John liked to stare at for hours on end, trying to predict which of the flashing red lights would wink on next. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 119)

Alex didn’t need to convince the Beatles that his gadgets had some practical value. He brought them an electric apple which pulsated light and music and a “nothing-box” which had twelve lights, ran for five years, and, as its name suggests, did exactly nothing. (Apple To The Core, p. 87)

To the London lads at the TV repair shop he was known simply as Yanni Mardas. In his spare time he built a box with a group of small lights on the front that flashed on and off in a random pattern. It was just a fun object with no practical application but seemed incredibly amusing to someone on an acid trip. (Many Years From Now, p. 373)

In the basement, hundreds of Nothing Boxes constructed by Magic Alex waited in the darkness, having blinked themselves to death. (The Love You Make, p. 280)

Paint That Changes Colour

Among the amazing devices he offered John was a car paint that would change color at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans, an electrostatic wallpaper that would make any room into a total sound chamber, and an artificial sun that would illuminate the night sky by means of laser beams. (The Lives Of John Lennon, p. 244)

“Another invention consisted of a thin piece of metal with something on it like a thick enamel paint, and it too had wires coming out of it. When it was connected, it lit up in a bright luminous greeny-yellow colour. Alex said, ‘Imagine if that was the back end of the car and you’d just stepped on the brake.’ So that’s what I wanted him to do. The Ferrari was going to be rubbed down to the bare metal and Alex was going to apply the magic coating. We asked, ‘Can you do other colours too?’ – ‘Sure, whatever you want.’

“We decided he was going to connect a colour scheme for the whole body of the car. The back of the car would be red – but only when you stepped on the brake! The rest of the time the whole car would be connected to the revs on the gearbox – so the car would start off quite dull, and as you shifted through the gears it would become brighter. You could go down the A3 and pass somebody and it would look like a flying saucer.” – George Harrison (The Beatles Anthology, p. 290-291)

Paint That Glowed Through Electricity

There were two perfect examples to invest in right under their noses: Magic Alex and The Fool. Magic Alex would be given a workshop in which to research and develop all of his wonderful inventions, including the paint that plugs in and lights up the wall. (The Love You Make, p. 255)

The Beatles were impressed by some electronic gadgetry he made for them and were intrigued by the various inventions he said he could devise, including an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations and a paint which glowed when connected to an electrical current. (The Encyclopedia Of Beatles People, p. 217)

“Magic Alex invented electrical paint. You paint your living room, plug it in, and the walls light up! We saw small pieces of metal as samples, but then we realized you’d have to put steel sheets on your living-room wall and paint them.” – Ringo Starr (The Beatles Anthology, p. 290)

Alex was certainly clever, a good electronic technician; but the boys pandered to his wildest whims. He would bring little toys into the studio as throwaway gifts, which of course pleased the boys. One day he came in with a little machine about half the size of a cassette, powered by a microcell battery. When it was switched on, it made a series of random bleeps.

‘Fantastic!’ said John. ‘You’ve made that?’

‘Oh, just a little gadget I knocked up in ten minutes,’ said Magic Alex. Then he would launch into the sales spiel. ‘That’s just to give an idea of the sort of thing we can do. Now, I’ve had an idea for a new invention. It’s a paint that, when I spray it on the wall, and connect it up to two anodes, will make the whole wall glow. You won’t need lights.’

‘Fantastic!’ said John.

‘Mind you,’ said Magic Alex. ‘I’ll need a little backing to set it up.’

‘Fantastic!’ said John. (All You Need Is Ears, p. 172)

Paint That Rendered Things Invisible

We also set Alex up with his own laboratory in a Boston Street warehouse, where he claimed to be putting the final touches on – among other things – his flying saucer and a new kind of paint that would render objects invisible. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 159)

Despite the lack of the promised artificial sun at the Apple boutique opening, Magic Alex had managed to remain in favour. His next projects were to be a flying saucer and magic paint that would render objects invisible: clearly both highly marketable inventions. This time his Boston Place workshop suffered a mysterious fire just before he unveiled his masterworks. It would obviously take months before he could produce new working prototypes so he bought himself another stay of execution. (Many Years From Now, p. 531-532)

Phasing Device For Guitars

Conversation on the set of Let It Be

10 January 1969

Cameraman: Roll 109A, slate 201A.

[…]

Glyn Johns: To change the subject, you know you were talking about this phasing device that Alexis has built for guitars, have you actually tried it out?

George Harrison: He hasn’t … you see, the thing is, when he … he just comes across things, you know, as he’s designing, so he just designs it and then he says ‘Oh yeah, I’ve done this.’ But he hasn’t actually made it, because he’s busy building recording studios.

Quad Speakers

Alex also rigged up Kenwood’s sound system with the first quadraphonic speakers I had ever heard. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 119)

Radio Shaped Like An Apple

Mavis Smith had no sooner finished with the French pop-magazine writer when an Italian journalist from Milano walked in to see if he could interview any of the Beatles for his magazine and a radio show from Rome on which he had 20 minutes air time every Thursday. He was very curious about progress on Magic Alex’s inventions, especially the transistorized radio shaped like an Apple that was going on the market at the unbelievably low price of ten shillings. (The Longest Cocktail Party, p. 106)

Aspinall says he and the Beatles were most impressed with a Magic Alex contraption, producing sound from a record player through a transistor radio without the use of any wiring.

“We sat down at a dinner table and Alex put a transistor radio on the table,” Aspinall remembers. “The radio was playing ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand,’ and at first we thought it was a song on the radio. Then we realized that the sound was coming from a record player through the transistor.”

Alex didn’t need to convince the Beatles that his gadgets had some practical value. He brought them an electric apple which pulsated light and music… (Apple To The Core, p. 86-87)

Radio Station

Magic Alex, who we were led to believe he had the genius of both Marconi and Edison combined, he told us so himself. George had once confided that Alex was designing a solar powered electric guitar, which, I assumed would be groovy for afternoon concerts. He had been summoned to India by John And George and was to build an electronic device that he promised to be not much bigger than a trash can lid. It was to be made out of humdrum electronic parts available at the local equivalent to Radio Shack and he modestly claimed that when assembled the device would not only supply the power for the gigantic radio station, that was to beam out to the far corners of the world, Maharishi's message of Meditation, Peace and Love but would have enough of a surplus to light up the entire region. Amazingly all that had to be done was for the device to be assembled and then placed at a strategic point in the Ganges. A little far fetched, maybe but whether it was the long meditations or the mind bending hallucinates we had all only recently given up I'm only a little embarrassed to say that it seemed like a great idea at the time. (Midnight In The Oasis)

“Magic Alex” Mardas was a friend of the Beatles who worked for Apple, planning several far-fetched inventions, including an electronic device that would transmit the Maharishi’s message around the world. (Lennon Remembers, p. 70)

The Maharishi’s most powerful critic turned out to be Magic Alex. Alex was summoned to Rishikesh by John, who missed his company. When Alex arrived at the ashram, he was appalled at what he found. “An ashram with four-poster beds?” he demanded incredulously. “Masseurs, and servants bringing water, houses with facilities, an accountant – I never saw a holy man with a bookkeeper!”

According to Alex, the sweet old women at the ashram Cynthia liked so much for their warmth and openness were “mentally ill Swedish old ladies who had left their money to the Maharishi. There were also a couple of second-rate American actresses. Lots of people went to India,” he said, “to find things they couldn’t find at home, including a bunch of lost, pretty girls.” Alex was disgusted to observe the Maharishi herding them together for a group photograph, like a class picture, which he would use for publicity.

It was also quite apparent that John was totally under the Maharishi’s control. John had been completely free of drugs and alcohol for over a month by the time Alex arrived, and he was the healthiest he had been in years, but Alex still felt the Maharishi was getting more than he was giving. Alex was at camp for only a week when he heard that the Maharishi expected the Beatles to tithe over 10 to 25 percent of their annual income to a Swiss account in his name. Alex reproved the Maharishi for this, accusing him of having too many mercenary motives to his association with the Beatles. Alex claims the Maharishi tried to placate him by offering to pay Alex to build a high-powered radio station on the grounds of the ashram so that he could broadcast his holy message to India’s masses. (The Love You Make, p. 261)

Radio Telephone

In the meantime, Magic Alex kept scepticism at bay by presenting the Beatles and their close friends and associates with a parade of ingenious novelties. To me he gave a radio that he’d built into a telephone – enabling me to dial the station of my choice like a phone number, and then listen to the program through the receiver. It was a lovely present – but it wasn’t exactly a flying saucer. (John Lennon In My Life, p. 160)

Recording Studio

“And do you have any idea what’s happening with the studio downstairs?”

“As far as I know, Alexis and Apple Electronics are supposed to be getting it together. I mean, it doesn’t function at all right now, but they tell me it’s going to be ready in two months. They say it’s going to be the best studio in town.” (The Longest Cocktail Party, p. 47)

Audio interview with Alan Parsons (audio engineer), 2001

Question: Alex Mardas’ weird console at Apple, any recollections of that?

Alan Parsons: Oh, my goodness. I mean, what a piece of junk. I mean, it really was unbelievable. I mean, held together with bits of strings and chewing gum was an understatement. I mean, it really was just the most unbelievable … the philosophies were the strangest things, eight tracks, eight faders, eight speakers, you know. It was really odd.

Question: Whatever happened to it?

Alan Parsons: Somebody bought it for £50. They were ripped off.

“Do you know how the sessions at Twickenham have been going?”

“From what I hear, it’s very tense. That film studio doesn’t help any, either. It’s too big, too cold and is the worst place to try and get an album together in. They turn the cameras on the minute they arrive and keep them going until they leave. Everyone is getting very uptight with everyone else.”

“Why don’t they move the setup to the basement here? After all, this is their building and they built the studios so they could work here after all those years at EMI.”

“Well, that’s what’s going to happen. They’ve already said, ‘Move it to Apple,’ but that’s going to take another week, because the downstairs studio, as you should know, is a mess. I mean, it looks beautiful, but nothing works.”

“What’s wrong with it?”

“Everything’s wrong with it. Only half of the eight tracks work, and sometimes the whole thing packs up. The studio isn’t even soundproof. You can hear people walking across the floor upstairs, and you can even pick up the bass vibrations from loud conversations. Sometimes, when there are a lot of people running around up there, it sounds like the ceiling is falling in.”

“Doesn’t sound very encouraging. Whose fault is it?”

“Well, Apple Electronics was supposed to be overseeing the whole thing, but there doesn’t seem to be any one person in charge of the whole setup. Magic Alex spends all his time over at Boston Place, and no one ever sees him and has no idea what inventions he’s inventing, but every once in a while you get the word that he’s working on something big and about to make a breakthrough. Who knows? If you’ll remember, his lab was going to be in the basement with the recording studio, but that doesn’t look like it’s going to materialize.”

“Wouldn’t it save more time if an outside team of engineers was called in and told, ‘Here, design a functioning studio for us’?”

“Well, there’s been some dialogue about that, but nothing ever came of it. And another big boo-boo is that the damn boiler that heats the building is located right in the studio; so you can’t record when it’s on, which means you have to turn it off, which means you have a building full of cold people and musicians with blue fingers.”

“So what’s going to happen now that they’ve said they want to finish the album here?”

“Everyone’s freaked out of course, running around in a blind sweat trying to get the control room working, but nothing seems to be making any sense there. So Glyn Johns isn’t going to have the easiest time, either.” (The Longest Cocktail Party, p. 92-93)

The final irony came when the boys decided that they were going to build their own studio in their building in Savile Row, and that it was going to be the best in the world. And who should they turn to for the design of this electronic Mecca? Why, Magic Alex, naturally. Once he had built it, the boys sat down to wait for the installation of the famous seventy-two-track machine. They waited. And waited. And finally, when we came to the recording of the album Let it Be, late in 1969, which they wanted to do in their own studio, they had to admit that Alex still hadn’t quite worked his miracle.

‘You’d better put some equipment in, then,’ they told me.

‘O.K., we’ll use mobile equipment,’ I said, and went back to EMI, whom I had left by then, to borrow some. With Keith Slaughter, and Dave Harries who eventually became my studio manager at AIR, I installed at Apple all the multi-track machines and other equipment necessary to make a proper recording – just for the one record. With that done, I examined the Alex-designed studio for its acoustic properties. For a start, there was very nasty ‘twitter’ in one corner. But our problems didn’t end there. Alex had overlooked one small detail: there was no hole in the wall between the studio and the control rooms. The only way to get the cables through was to open the door and run them along the corridor.

Another thing – the heating plant for the entire building was situated in a little room just off the studio. And since the sound insulation was not exactly magical, every now and then in the middle of recording there came a sound like a diesel engine starting up.

Apart from these minor points, I suppose, it wasn’t a bad attempt at studio design.

But that was Apple, and I suppose it is ironic that the man brought in to clear up the administrative mess, Allen Klein, who tightened up the control and put things on a proper basis, should also have been the man who because of Paul’s dislike of him was a great factor in the final break-up of the Beatles. (All You Need Is Ears, p. 173-174)

The delay lay in the fact that Apple Corps had an offshoot company called Apple Electronics, run by a Greek closely befriended by the Beatles, Alexis Mardas. Alexis was so clever in his field that he was dubbed ‘Magic Alex’ by the group and, installed in their Savile Row office in July 1968, they asked him to install a basement recording studio. Mardas promised miracles. Abbey Road had eight-track facilities. Apple would have 72. And away with those awkward studio “baffles” around Ringo and his drum kit! (Placed there to prevent leakage of the drum sound onto the other studio microphones.) Magic Alex would install an invisible sonic beam, like a force field, which would do the work unobtrusively.

Hardly surprisingly, it all worked out very differently…

“The mixing console was made of bits of wood and an old oscilloscope,” recalls Dave Harries. “It looked like the control panel of a B-52 bomber. They actually tried a session on this desk, they did a take, but when they played back the tape it was all hum and hiss. Terrible. The Beatles walked out, that was the end of it.” Keith Slaughter, Harries’ colleague, remembers, “George Martin made a frantic call back to Abbey Road. ‘For God’s sake get some decent equipment down here!’”

Alan Parsons, later a top engineer and producer and, later still, the man behind the highly successful Alan Parsons Project, was in January 1969 a teenage tape operator newly employed at Abbey Road, and he went down to Apple along with the borrowed equipment. He too clearly remembers Mardas’s invention. “The metal was an eighth of an inch out around the knobs and switches. It had obviously been done with a hammer and chisel instead of being properly designed and machined. It did pass signals but Glyn Johns said ‘I can’t do anything with this. I can’t make a record with this board’.” Abbey Road duly lent Apple two four-track consoles to go with its own 3M eight-track tape machine.

And what happened to Magic Alex’s rejected masterpiece? “The mixing console was sold as scrap to a secondhand electronics shop in Edgware Road for £5,” says Geoff Emerick. “It wasn’t worth any more.” (The Beatles Recording Sessions, p. 164-165)

Conversation on the set of Let It Be

10 January 1969

Cameraman: Roll 109A, slate 201A.

[…]

Glyn Johns: To change the subject, you know you were talking about this phasing device that Alexis has built for guitars, have you actually tried it out?

George Harrison: He hasn’t … you see, the thing is, when he … he just comes across things, you know, as he’s designing, so he just designs it and then he says ‘Oh yeah, I’ve done this.’ But he hasn’t actually made it, because he’s busy building recording studios.

Alex had been complaining for months that the equipment in EMI was out of date, that the Beatles were being fobbed off with second-rate facilities; he boasted that he could design and build a seventy-two-track studio for them that would be the most advanced facility on earth. It must have come as a shock when they finally called his bluff and asked him to do just that, though not without some serious misgivings being voiced by George Martin. Martin wrote in his autobiography All You Need Is Ears:

I confess I tended to laugh myself silly when they came and announced the latest brainchild of Alex’s fertile imagination. Their reaction was always the same, ‘You’ll laugh on the other side of your face when Alex comes up with it.’ But of course he never did … The trouble was that Alex was always coming to the studios to see what we were doing and to learn from it, while at the same time saying, ‘These people are so out of date.’ But I found it very difficult to chuck him out, because the boys liked him so much. Since it was very obvious that I didn’t, a minor schism developed.

PAUL: When we came to do something like a studio, or something electronic, if you’ve got a company called Apple Electronics, how could you bypass it? How could you not ask him to be involved? So Alex said, ‘Yes, of course I can do a studio. Of course I can!’ Whereas I would think, Of course I can do this. I can oversee it, with a team of very good engineers that I could talk to. I’m not sure Alex had a team of very good engineers. It was all a little bit of a solo effort and people like George Martin, being the voice of reason, would be tearing their hair out at that kind of thing. But Alex was Apple Electronics and he’d promised faithfully he could do it, so you had to give him a chance at it. You can’t bring someone else in and say, ‘This is the proper person,’ because then the insinuation is, ‘Why isn’t the proper person running our company?’ It would have all got much too close to home, I think. So that was one of those things. And in the end it was gutted. (Many Years From Now, p. 532)

“Originally, the studio was going to be seventy-two track, which was pretty far out in 1968. We bought some huge computers from British Aerospace in Weybridge, and put them in my barn in St George’s Hill. Birds lived in them, mice lived in them – but they never left that barn. It was a far-out idea, but once again Alex never came through. We’d just graduated to eight track – God knows what we thought we were going to do with seventy-two.” – Ringo Starr (The Beatles Anthology, p. 291)

“At the instigation of Magic Alex, meanwhile, Apple acquired a pair of second-hand computers. A decade before the advent of the mass-produced microcomputer, Alex had prophetically assured us that these unwieldy machines were both the wave of the future and a steal at £20,000 apiece. The only problem was that nobody – not even Alex – could figure out what to use them for, let alone how to operate them. In the end, the computers were simply left to gather dust in Ringo’s garage.” – Pete Shotton & Nicholas Schaffner (John Lennon In My Life, p. 159)

“When we finally got him to make a recording studio, we walked in and it was chaos. It was the biggest disaster of all time. He was walking round with a white coat on like some sort of chemist, but didn’t have a clue what he was doing. It was a sixteen-track system, and he had sixteen little speakers all around the walls. You only need two speakers for stereo sound. It was awful. The whole thing was a disaster and had to be ripped out.” – George Harrison (The Beatles Anthology, p. 291)

“Magic Alex said that EMI was no good, and he could build a much better studio. Well, he didn’t, and when we recorded in Savile Row I had to equip it with EMI gear. The Apple offices were pretty sparse at that time, clinical and groovy with white paint – a nice place to be – but the studios were hopeless, because they were just empty rooms. In fact Magic Alex, for all his technical expertise, had forgotten to put any holes in the wall between the studio and the control room, so we had to run the cable out through the door, and we had a nasty twitter in one corner that came from the air-conditioning which we had to switch off whenever we made a record. Apart from that, it was ideal!” – George Martin (The Beatles Anthology, p. 318)

“By January 20th they decided to move to Savile Row. Alexis Mardas was building a studio there, although it wasn’t finished. The control room and the console had wires everywhere, so they had to take the portable equipment in there. But the studio itself, the actual room to play in, was much nicer, much cosier and they were much more at home.” – Neil Aspinall (The Beatles Anthology, p. 318)

“George Harrison: ‘Alex’s recording studio at Apple was the biggest disaster of all time. He was walking around with a white coat on like some sort of chemist but didn’t have a clue what he was doing. It was a sixteen-track system and he had sixteen little tiny speakers all around the walls. You only need two speakers for stereo sound. It was awful. The whole thing was a disaster and had to be ripped out.’

“John Dunbar: ‘It was absurd. If you’d had a few Revoxes you’d have done better … He’d charge them thousands and buy the stuff second-hand. But John just wouldn’t listen at that stage; I mean, it was Magic Alex, then Maharishi, then this, then that …’

“The studio was unusable. There was an eight-track Studer tape recorder but no mixing desk for it. There was no soundproofing, so the lower vibrations of loud conversations in other rooms seeped in. The floorboards of the room above creaked whenever anyone walked over them; if someone ran it sounded as if the roof was falling in. Alex had built the studio right next to the heating plant for the entire building so recording would have been interrupted every time the central-heating unit fired up. But in fact no recording was actually possible at all because he had completely neglected one vital point. Alex had forgotten to make connecting ports between the control room and the studio, which meant that there was no way of getting microphone leads from the studio to the mixing desk. George Martin borrowed a pair of four-track mixing consoles from EMI and the microphone cables were run down the corridor with the door open, with consequent leakage. Martin was so fed up with what he regarded as the Beatles’ folie de grandeur that he left much of the recording to engineer/producer Glyn Johns, though Johns’s final mixes were never released. John finally had to accept not only that Alex had not delivered, but that he didn’t know the first thing about recording technology. The studio was eventually torn out without ever being used. Magic Alex disappeared. Not one of his ideas had ever materialized.” – Barry Miles (Many Years From Now, p. 532-533)

The recording studio in the basement has been an enormous drain on resources, too. The whole place has been converted at enormous cost, with no end of problems caused by a central heating boiler house sited just behind one of the thin walls. For a while, you could hear every gurgle and whoof that the boiler made! All this time Alexis is still promising to build his space-age thirty-two track recording desk. That hasn’t appeared so far, but it wouldn’t surprise me if he managed it. God knows what such a machine would cost, though. (Yesterday: The Beatles Remembered, p. 195)

Solar-Powered Electric Guitar

Magic Alex, who we were led to believe he had the genius of both Marconi and Edison combined, he told us so himself. George had once confided that Alex was designing a solar powered electric guitar, which, I assumed would be groovy for afternoon concerts. He had been summoned to India by John And George and was to build an electronic device that he promised to be not much bigger than a trash can lid. It was to be made out of humdrum electronic parts available at the local equivalent to Radio Shack and he modestly claimed that when assembled the device would not only supply the power for the gigantic radio station, that was to beam out to the far corners of the world, Maharishi's message of Meditation, Peace and Love but would have enough of a surplus to light up the entire region. Amazingly all that had to be done was for the device to be assembled and then placed at a strategic point in the Ganges. A little far fetched, maybe but whether it was the long meditations or the mind bending hallucinates we had all only recently given up I'm only a little embarrassed to say that it seemed like a great idea at the time. (Midnight In The Oasis)

Voice-Recognition Telephone

Alex’s original ideas were all theoretically possible given the existing technology, though the computing power needed at that time would have made them prohibitively expensive: they included a telephone that you told whom you wanted to call, which dialed the number using voice recognition, and one that displayed the telephone number of an incoming call before you answered, both of which were already in prototype at the Bell Telephone labs in New York, though the Beatles didn’t know that. (Many Years From Now, p. 375)

On another occasion Paul came in to tell me about Magic Alex’s idea for a telephone invention. ‘You know, we’re so out of date with our telephones in this country,’ he said. ‘But Alex is working on something. We won’t even need telephone directories. I’ll be in my drawing-room, and I’ll just say, “Get me George Martin,” and the phone will hear that and be computerised to understand the words. It’ll automatically dial your number, and you’ll be on the other end of the phone, and I won’t have to do anything about it. It’s so simple with computerisation, and Alex has got it all worked out.

‘Really?’ I said.

I confess that I tended to laugh myself silly when they came and announced the latest brainchild of Alex’s fertile imagination. Their reaction was always the same: ‘You’ll laugh on the other side of your face when Alex comes up with it.’ But of course he never did. (All You Need Is Ears, p. 172-173)

“Also, he had the ‘talking telephone’ (remember this is 1968) – a speaker-phone, which compensated so the volume always stayed at the same level as you walked round the room.” – Ringo Starr (The Beatles Anthology, p. 290)

“As I say, this was John’s doing. This was John’s guru, but we were all fascinated by the talk, which was rather sci-fi but the idea being that you could do it now. In the sixties there was this feeling of being modern, so much so that I feel like the sixties is about to happen. It feels like a period in the future to me, rather than a period in the past.

“I was just going along with the thing. We committed ourselves with Apple Electronics to make the little gadgets of tomorrow: the wallpaper loudspeaker, the phone that would respond to voice commands. We were thinking this could happen in five years, whereas it’s taken a little longer. A lot of it is still not online but I think it’s accepted that it will be, so we weren’t being stupid, but we were probably overreaching. We were thinking, if he’s got a little place, he may be able to come up with something. Then we’d involve some big electronics giant and say, ‘Come on, Grundig, we’ve patented this. Surely you’ll want this? You could make it great.’ We were on to all those sort of schemes but I don’t think it was so much to make money as to move things ahead. So the scientific ideas would be available.

“We were doing the wallpaper speakers so we could have them! Then I think it just ran on. Our friends would want them too, so that’d be a few more, and then, why not let everyone have them? I’m trying to remember why we even bothered getting involved now. Hopefully for all the right reasons. So we were committed to this electronics company which we registered and he was in some back room trying to develop something. I’m not sure what. I was a bit suspicious. ‘Well, what’s he got then? What is it we’re working on? Is it the loudpaper?’ I always sensed that there wasn’t going to be a product there, and it was a bit of a wild-goose chase and we’d move on from that to the next thing.” – Paul McCartney (Many Years From Now, p. 442-443)

Alex’s workshop is in a little mews just behind Marylebone Station and he called me there one day. When I arrived, he was sitting at his desk with his telephone in front of him and his arms crossed.

‘Hello, Alistair. We call you office now.’

Without moving to his telephone he just spoke my number into thin air. I looked at him as if to say, ‘So?’ A noise of ringing came into the room, then a voice I recognized said, ‘Mr Taylor’s secretary.’

‘OK. It is me, Alex.’

‘Oh,’ replied my secretary. ‘He’s just coming over to see you.’

‘OK. Thank you.’

A perfectly ordinary, even boring telephone conversation, you’ll think. But Alex rang my office, spoke with my secretary and broke the connection all without moving from his seat or touching his telephone! The machine was sensitive to his voice pattern, so that all he had to do was speak into it the number that he wanted to reach and the phone would automatically make the connection! I even checked with my secretary when I went back to the office. Yes, Mr Mardas had called. Now there is magic, without a doubt. If the business world knew about an invention like that, there would be mobs outside Alex’s workshop greater than the hordes who used to besiege Beatles concerts! (Yesterday: The Beatles Remembered, p. 146)

X-Ray Camera

From these he moved on to greater flights of imagination: an X-ray camera that could see through walls, so you could see people in bed or in the shower. (Many Years From Now, p. 375)

Interview with Alan Parsons (audio engineer), 2001

Alan Parsons: Oh, my goodness. I mean, what a piece of junk. I mean, it really was unbelievable. I mean, held together with bits of strings and chewing gum was an understatement. I mean, it really was just the most unbelievable … the philosophies were the strangest things, eight tracks, eight faders, eight speakers, you know. It was really odd.

Question: Whatever happened to it?

Alan Parsons: Somebody bought it for £50. They were ripped off.

Conversation on the set of Let It Be

10 January 1969

Cameraman: Roll 109A, slate 201A.

[…]

Glyn Johns: To change the subject, you know you were talking about this phasing device that Alexis has built for guitars, have you actually tried it out?

George Harrison: He hasn’t … you see, the thing is, when he … he just comes across things, you know, as he’s designing, so he just designs it and then he says ‘Oh yeah, I’ve done this.’ But he hasn’t actually made it, because he’s busy building recording studios.

Michael Lindsay-Hogg: Where did you get Alexis from?

George: He just came to England.

Glyn: He worked for Pye Co. Television…

George: No, he was in England, and he was in the museum looking at the Greek things in a museum in England, and he met John Dunbar, or John Dunbar met him, and was talking to him. And then asked him if he’d … ‘cause Alex was only supposed to be here for a few days, they asked him if he’d stay and build a light machine for the Stones’ tour.

Michael: Yeah.

George: So he stayed, and did that, and then he stayed with Dunbar. Oh, then he met John, and then he met us. And he’s been there ever since.

Michael: Is that device he’s going to put on records going to work?

George: Yep.

Michael: Where you can’t tape it? Great idea.

Ringo: If it gets put on.

Michael: But surely, I mean, it’s in the interests of all the people who put out records to have it on.

Ringo: Yeah, but it’s…

Michael: Not in the interest of people who make tape machines.

Ringo: I mean, I, I think it should be on, but John thought it was ‘bad Beatles’. Stopping all the kids taping it.

George: Yeah, but the thing is the Beatles now, in America they have, you know, those cassette tapes. Well that means that uh, it’s easy. Somebody just gets, buys one, even. And then rolls off their own few million and sell it. And there’s, you know, everybody loses out on that, because people who bought it, and yet some cunt’s made all the money, for doing fuck all except thieving it.

Ringo: Did you hear it about, you know, the signal that they’re putting on, you could put adverts on it.

Michael: Yes, well the one Neil talked about is ‘this is Apple Records’.

George: Messages or talking anything, you know, like…

Michael: Yes, ‘please … please come home, all is forgiven’. It’s a great idea, I think. Because basically, if you’re rich enough to have a tape recorder, you’re rich enough to buy a record, really.

Friday, July 21, 2006

Interview: John Lennon, London - May 2, 1969

Date: 2 May 1969

Time: 12:30 - 1:00 pm

Location: Studio G, Lime Grove Studios, London

Interviewer: Michael Wale

Broadcast: 2 May 1969, 10:55 - 11:35 pm

BBC1: How Late It Is

. . . are John Lennon and Yoko Ono, whose new film, The Rape . . . John and Yoko have come to the studio tonight to talk to Michael Wale and to show us part of their film.

YOKO: Well, this is a film about life. And so, you can just take ten minutes or twenty minutes, any time out of it and it works. But, it's about, especially about contemporary life, where people are constantly exposing each other and prying into each other's life and causing tension from that.

JOHN: It's also in a foreign language.

YOKO: Well, we're all talking foreign languages to each other, you know.

JOHN: The point is it doesn't matter what she says. All she's really saying, all the time 'Why me? Of all the people in the world?'

YOKO: But I'm saying that all the time it's the world, you know, we're always saying that 'Why me? Why me?' you know.

JOHN: You asked for it that's why.

YOKO: And our language is very foreign to other people's things, you know.

MICHAEL WALE: Can you tell me first of all how you set about making this film?

JOHN: Well, Yoko had what she calls a script, which is 'Let's make a film about . . .' you know, like that. And we were in hospital and I was having my miscarriage and we did it from the hospital, you know. And we got the cameraman Nick and said, 'Now you go out and chase somebody about, Nick'. So he went and he did about half a dozen test runs on different people, in Hyde Park, there's some good stuff, he never went on long enough because he was a kind guy, he didn't want to intrude, you know, but the idea was to intrude. And the whole bit is try not react to the camera, but after that half an hour, 'I think you have to give an explanation, old man'. But none of that went far enough, you know. So he went out, and I don't know how many days he went out, maybe about a week or two and he finally came up with the girl, you know.

MICHAEL WALE: Now this girl, was she an actress?

JOHN: Well, somebody in Montreux said, 'Did you know this girl had actually played . . ' you know, and it was probably something like Alice In Wonderland at school, I don't know what she's been doing. Whether she was an actress . . . we didn't know.

YOKO: She's modelling now.

JOHN: She's modelling now, so I think she'll turn into an actress, you know. But I don't think she was. But some guy said she was and she might have been, but if she's an actress, she gets an Oscar for that, she's not acting in that. That's real.

MICHAEL WALE: And this girl, she didn't really know why she was being followed?

JOHN: No, what she's saying all the time is 'What is this?' You know, everybody reacts the same at first, 'Is this the television, am I on?' you know and they're all a bit happy about it. And after about a half an hour they get a bit uncomfortable, you know, they go through all these changes. And they start saying, 'Well, what is it?' We told the cameraman and the soundman not to answer, because then they communicate and they become sort of friends, you know, something happens between them. So then say, 'What is it for? Please tell me what it's about' and it goes on and on like that. And all she ever says almost, is 'What is it? What is it?'

MICHAEL WALE: Now it is about intrusion, but who are the intruders?

JOHN: Well, we all intrude on each other, you know, always spying and looking through the curtains down the road and watching each other's lives, and everybody watches everybody and the press watch everybody and we watch the press, just everybody really.

YOKO: Well, we're all peeping Toms, you know.

MICHAEL WALE: Well, that in fact, on the back of your new LP.

JOHN: Out today, but tomorrow for the full special.

MICHAEL WALE: Shows you coming out court and police surrounding you, not exactly grinning. That was after you were on a drugs charge. Were they intruders?

JOHN: Well, I mean, it's their job, it's called to intrude, but at that time they were helping us get out. So that's how friendly they look when they're helping. But that really tells the whole story, you know.

MICHAEL WALE: When they arrived at your house, what happened? The cops would have knocked at the door. . .

JOHN: Oh, well, it was a bit strange, because we were lying a-bed, as is our wont, and there was a sort of knock, and Yoko opens the door, doesn't open it, it's one of those flat bits, she goes to the front door and says, 'Who is it?' and a voice says 'Uh, I'm the postman,' said a woman's voice. And Yoko says, 'A postman is a man!' And then, 'I have a special message for you,' and Yoko, we're panicking, because it's either the press or some mad fan, so anybody that knocks like that. So, this goes on for a bit, so she's too intrigued, . . . the fucker opens the door, excuse me, and I'm still in the bed but I can hear it going on, and I just stop in a peep and there's a few people at the door, all in plain clothes, so you couldn't tell what it was. So she runs back in, 'What is it? What is it?' And she's all panicking and pregnant and that, 'What is it? What is it?' People at the door and all that. And she's just sort of recovering on the floor, and there's this banging on the window, I thought, oh, they've got me, you know, not the police, but whoever it is that's trying to get me. And I open the curtains and this giant, like super-policeman is against the window, and we didn't have any clothes on, just sort of nighties, the guy is against the window, I'm trying to hold it down, 'What is it? What is it?' And he says, 'Huuuuuuh!' And I don't know whether he said 'I'm the police' I never heard it, but I'm saying, 'Ring, ring the police' you know. And it just went on, it was like Marx Brothers, but it didn't feel like that at the time.

MICHAEL WALE: But in fact, these were pressures on you, and do the pressures, have they affected your life, and in there, in fact that was during your miscarriage.

YOKO: Well, everything affects our life, you know. But life is pretty exciting.

MICHAEL WALE: Our program tonight is mainly about nostalgia, are you nostalgic about anything John?

JOHN: Each other and yesterday, you know.

MICHAEL WALE: Yoko?

YOKO: About us, you know. About John and Yoko meeting, and about today. About the future.

MICHAEL WALE: John and Yoko then, thank you very much.

JOHN: Pleasure.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Interview: John Lennon, Ascot - March 1971

Location: Tittenhurst, London Road, Sunningdale, Ascot

Interviewer: Kenny Everett

Broadcast: Radio Monte Carlo

KENNY EVERETT: Now, over to Ascot. Well listeners, here we are in John's luxurious 72-acre studio, here built into his home here at Ascot.

JOHN: We are.

KENNY EVERETT: Seeing as this isn't television...

JOHN: Yes, we're in the studio, 5x8.

KENNY EVERETT: Now, why did you buy a studio in your own house, when you've got one in your office as well? In fact, how many have you got?

JOHN: Well, the one in the office hasn't been finished, you see. And that's going to be 16-track, and this is 8-track. And it just means you can chord when you want. And, you can go to bed.

KENNY EVERETT: Or have a cup of tea.

JOHN: Right.

KENNY EVERETT: If ever you feel during this interview like coming out with an original song, recorded just for radio Monte Carlo, please feel free.

JOHN: (singing) The man that broke the bank of Monte Carlo.

KENNY EVERETT: Oh my god. Well tell us about your LP, John. It seems not to be as jolly as your last ones.

JOHN: Jolly as what?

KENNY EVERETT: Well, as the rest of them.

JOHN: Well, such as?

KENNY EVERETT: Revolver, Sgt. Pepper...

JOHN: Ah, well that was a group effort, you see.

KENNY EVERETT: Do you reckon yourself the sad member of the group?

JOHN: Well, I wouldn't say they're all particularly much happier than me. But, they might emphasize the happier side, that's all.

KENNY EVERETT: Are you thinking of doing a jolly album?