- Beatles Photos Up For Auction (BeatCrave.com)

- Quick Hits: Bon Jovi, Rihanna, AFI, John Mayer, Lady Gaga, The Beatles (FMQB)

- Beatles catalog is temporarily banned from music website BlueBeat (Los Angeles Times)

- Beatles Come to Apple -- No, Not that Apple (PC World)

- Dhani Harrison: Rock Band 3 will Teach You to Play Music (Kombo.com)

- The Best Beatle (Business Standard)

- Beatles song helps Jack give sister gift of life (WalesOnline)

Pages

▼

Saturday, November 07, 2009

Beatles News

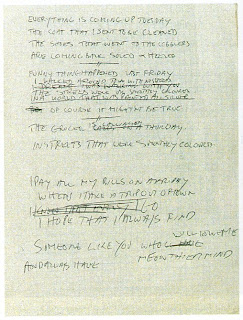

"While My Guitar Gently Weeps" Lyrics

by George Harrison

Original Manuscript (1968)

Original Manuscript (1968)

Tampering - tapering, Tempering, Thundering

Tittering, Tottering, Towering, Toppling

Wandering, Watering, Wavering, Weathering

Whispering, Wintering, Whispering, Wondering

and love that sleeps

whilst my guitar gently weeps

I look at you all see the love there that's sleeping

While my guitar gently weeps.

I look at the floor and I see it needs sweeping

Still my guitar gently weeps.

I don't know why - nobody told you, how to

unfold your love

I don't know how, someone controlled you, how they

blindfolded you.

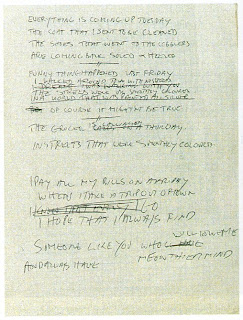

Second Manuscript, "While My Guitar (Gently Weeps)" (1968)

Second Manuscript, "While My Guitar (Gently Weeps)" (1968)

I look at you all see the love there's that's

sleeping... While my guitar gently weeps.

The problems you sow are the troubles you're reaping

still my guitar gently weeps ....

I don't know why...nobody told you, how to unfold

your love .... I don't know how, someone controlled

you, they bought and sold you

I look at the world, and I notice it's turning

while my guitar gently weeps

With every mistake we must surely be learning

Still my guitar gently weeps

I don't know why, you were diverted, you were

perverted too. I don't know how...you got inverted

no one alerted you

I look at the trouble and hate that is raging

while my guitar gently weeps

as I'm sitting here doing nothing but ageing

still my guitar gently weeps.

As Released by the Beatles (1968)

As Released by the Beatles (1968)

I look at you all, see the love there that's sleeping

While my guitar gently weeps.

I look at the floor and I see it needs sweeping

Still my guitar gently weeps.

I don't know why nobody told you how to unfold your love

I don't know how someone controlled you

They bought and sold you.

I look at the world and I notice it's turning

While my guitar gently weeps.

With every mistake we must surely be learning

Still my guitar gently weeps.

(Aah - aah)

I don't know how you were diverted

You were perverted too

I don't know how you were inverted

No-one alerted you.

I look at you all, see the love there that's sleeping

While my guitar gently weeps.

Look, look at you all

Still my guitar gently weeps ((eee)).

Oh, oh, oh - oh, oh.

Oh - oh, oh - oh, oh - oh, oh ((eee)).

Oh - oh, oh - oh, oh - oh ((eee)).

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah ((eee))

Oh - wuh ... ((eee)).

Original Manuscript (1968)

Original Manuscript (1968)Tampering - tapering, Tempering, Thundering

Tittering, Tottering, Towering, Toppling

Wandering, Watering, Wavering, Weathering

Whispering, Wintering, Whispering, Wondering

and love that sleeps

whilst my guitar gently weeps

I look at you all see the love there that's sleeping

While my guitar gently weeps.

I look at the floor and I see it needs sweeping

Still my guitar gently weeps.

I don't know why - nobody told you, how to

unfold your love

I don't know how, someone controlled you, how they

blindfolded you.

Second Manuscript, "While My Guitar (Gently Weeps)" (1968)

Second Manuscript, "While My Guitar (Gently Weeps)" (1968)I look at you all see the love there's that's

sleeping... While my guitar gently weeps.

The problems you sow are the troubles you're reaping

still my guitar gently weeps ....

I don't know why...nobody told you, how to unfold

your love .... I don't know how, someone controlled

you, they bought and sold you

I look at the world, and I notice it's turning

while my guitar gently weeps

With every mistake we must surely be learning

Still my guitar gently weeps

I don't know why, you were diverted, you were

perverted too. I don't know how...you got inverted

no one alerted you

I look at the trouble and hate that is raging

while my guitar gently weeps

as I'm sitting here doing nothing but ageing

still my guitar gently weeps.

As Released by the Beatles (1968)

As Released by the Beatles (1968)I look at you all, see the love there that's sleeping

While my guitar gently weeps.

I look at the floor and I see it needs sweeping

Still my guitar gently weeps.

I don't know why nobody told you how to unfold your love

I don't know how someone controlled you

They bought and sold you.

I look at the world and I notice it's turning

While my guitar gently weeps.

With every mistake we must surely be learning

Still my guitar gently weeps.

(Aah - aah)

I don't know how you were diverted

You were perverted too

I don't know how you were inverted

No-one alerted you.

I look at you all, see the love there that's sleeping

While my guitar gently weeps.

Look, look at you all

Still my guitar gently weeps ((eee)).

Oh, oh, oh - oh, oh.

Oh - oh, oh - oh, oh - oh, oh ((eee)).

Oh - oh, oh - oh, oh - oh ((eee)).

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah ((eee))

Oh - wuh ... ((eee)).

When the Beatles Met Elvis

Read by Chris Hutchins

Written by Chris Hutchins with Peter Thompson

Duration 4 hours

The Untold Story Of Their Entangles Lives

No one laughed more loudly than the King himself when the Beatles' manager, Brian Epstein, boasted 'My boys are going to be bigger than Elvis Presley.' It was the early sixties, and Presley, a living legend, appeared unassailable. Yet, in 1964, John, Paul, George and Ringo suddenly topped the American charts - and Beatlemania rolled the King in the greatest rock coup of all time.

Chris Hutchins, then a music journalist in his early twenties,was at the eye of the hurricane as the Beatles swept all before them. No other writer grew as close to the Fab Four from Liverpool as they conquered the world.

As America turned on to the Beatles in a big way during their 1965 tour, Chris Hutchins used his extensive network of connections to mastermind the greatest rock summit meeting ever: a one-and-only rendezvous between the King and the pretenders who were seizing his throne.

With co-author Peter Thompson, Hutchins draws on his own exclusive sources and unpublished personal archives, as well as FBI files and explosive dossiers from the District Attorney's investigators in Memphis, to probe into the greatest rock story never told - one in which the lives of Elvis Presley and the Beatles became dramatically entwined. They reveal the passions and the powerplay, the corruption and the conspiracies, the vendettas and the vanity behind pop-culture's greatest phenomena.

No book has ever penetrated so deeply into the secret worlds of Elvis and the Beatles. This is the graphic, firsthand account of the ambition, lust and greed that drove the most gilded icons in pop history to the very peak of the mountain. And of the dark and dangerous forces that destroyed them.

Written by Chris Hutchins with Peter Thompson

Duration 4 hours

The Untold Story Of Their Entangles Lives

No one laughed more loudly than the King himself when the Beatles' manager, Brian Epstein, boasted 'My boys are going to be bigger than Elvis Presley.' It was the early sixties, and Presley, a living legend, appeared unassailable. Yet, in 1964, John, Paul, George and Ringo suddenly topped the American charts - and Beatlemania rolled the King in the greatest rock coup of all time.

Chris Hutchins, then a music journalist in his early twenties,was at the eye of the hurricane as the Beatles swept all before them. No other writer grew as close to the Fab Four from Liverpool as they conquered the world.

As America turned on to the Beatles in a big way during their 1965 tour, Chris Hutchins used his extensive network of connections to mastermind the greatest rock summit meeting ever: a one-and-only rendezvous between the King and the pretenders who were seizing his throne.

With co-author Peter Thompson, Hutchins draws on his own exclusive sources and unpublished personal archives, as well as FBI files and explosive dossiers from the District Attorney's investigators in Memphis, to probe into the greatest rock story never told - one in which the lives of Elvis Presley and the Beatles became dramatically entwined. They reveal the passions and the powerplay, the corruption and the conspiracies, the vendettas and the vanity behind pop-culture's greatest phenomena.

No book has ever penetrated so deeply into the secret worlds of Elvis and the Beatles. This is the graphic, firsthand account of the ambition, lust and greed that drove the most gilded icons in pop history to the very peak of the mountain. And of the dark and dangerous forces that destroyed them.

Friday, November 06, 2009

"Please Please Me" Lyrics

by John Lennon and Paul McCartney

As Released by the Beatles (1963)

Last night I said these words to my girl

I know you never even try girl

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Please please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

You don't need me to show the way love

Why do I always have to say love

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Please please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

I don't want to sound complaining

But you know there's always rain

In my heart (in my heart).

I do all the pleasing with you

It's so hard to reason with you, whoa - yeah

Why do you make me blue?

Last night I said these words to my girl

I know/why do you never even try girl

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Please please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

Please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you

Please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

As Released by the Beatles (1963)

Last night I said these words to my girl

I know you never even try girl

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Please please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

You don't need me to show the way love

Why do I always have to say love

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Please please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

I don't want to sound complaining

But you know there's always rain

In my heart (in my heart).

I do all the pleasing with you

It's so hard to reason with you, whoa - yeah

Why do you make me blue?

Last night I said these words to my girl

I know/why do you never even try girl

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Come on (come on), come on (come on)

Please please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

Please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you

Please me, whoa - yeah

Like I please you.

Beatles News

- Beatles copyright case down a legal rabbit hole (CNET News)

- 'Mad Men' plots we'd like to see (Newsday)

- Beatles Ban Takes Effect at BlueBeat (PC World)

- Zemeckis Hopes to Recruit Beatles for “Yellow Submarine” (Rolling Stone)

- Judge Stops 2 Web Sites From Selling Beatles Songs (ABC News)

- Guitar Hero 5 keeps up with The Beatles (Play.tm)

- A Beatle in Town (Indian Express)

- First Look: Comme des Garcons x The Beatles (NBC New York)

"Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!"

"Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" is a song from the 1967 Beatles album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. It was composed primarily by John Lennon with input from Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon/McCartney.

Inspiration

Lennon wrote the song taking inspiration from a nineteenth century circus poster for Pablo Fanque's circus which he purchased in an antique shop on 31 January 1967 while filming the promotional video for the song "Strawberry Fields Forever" in Kent. Mr. Kite is believed to be William Kite, who worked for Pablo Fanque from 1843 to 1845.

Recording

One of the most musically complex songs on Sgt. Pepper, it was recorded on 17 February 1967 with overdubs on 20 February (organ sound effects), 28 March (harmonica, organ, guitar), 29 March (more organ sound effects), and 31 March. Lennon wanted the track to have a "carnival atmosphere," and told producer George Martin that he wanted "to smell the sawdust on the floor." In the middle eight bars, multiple recordings of fairground organs and calliope music were spliced together to attempt to produce this request; after a great deal of unsuccessful experimentation, George Martin instructed Geoff Emerick to chop the tape into pieces with scissors, throw them up in the air, and re-assemble them at random.

On 17 February, Lennon sings "For the benefit of Mr. Kite" in a joke accent, just before Emerick announces, "For the Benefit of Mr. Kite!, this is take 1." Lennon immediately responds, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" reinforcing his title preference, a phrase lifted intact from the original poster. The exchange is recorded in The Beatles Recording Sessions (slightly misquoted) and audible on track 8 of disc 2 of Anthology 2.

Although Lennon once said of the song that he "wasn't proud of that" and "I was just going through the motions," in 1980 he described it as "pure, like a painting, a pure watercolour."

It was one of three songs from the Sgt. Pepper album that was banned from playing on the BBC, supposedly because the phrase "Henry the Horse" combined two words that were individually known as slang for heroin. Lennon denied that the song had anything to do with heroin.

Personnel

* John Lennon: double-tracked lead vocals and harmony vocals; Hammond organ and piano; tape loops and harmonica.

* Paul McCartney: acoustic guitar and bass.

* George Harrison: harmonica and tambourine.

* Ringo Starr: drums and harmonica.

* George Martin: harmonium, Lowry organ, glockenspiel and tape loops.

* Mal Evans: harmonica.

* Neil Aspinall: harmonica.

* Geoff Emerick: tape loops.

Covers and influence

* The song is performed by The Bee Gees and George Burns in the 1978 film Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

* Serbian new wave band Električni Orgazam recorded a version on their 1983 cover album Les Chansones Populaires.

* Scottish comedian Billy Connolly recorded a mostly spoken-word recording of the song for the George Martin compilation In My Life.

* In 2004 Branimir Krstic released a classical guitar version of the song on the first full classical cover album of Sgt. Pepper.

* In the film Across the Universe, Eddie Izzard appears in a cameo and does a cover of the song in a spoken form.

* Avant-garde band The Residents performed a cover of the song at a 40th Anniversary celebration of Sgt. Pepper with the London Sinfonietta.

* Les Fradkin has an instrumental cover in his 2007 release "Pepper Front To Back."

* Swedish metal band Mister Kite take their name from the song title.

* Reggae band Easy Star All-Stars covered the song in the album Easy Star's Lonely Hearts Dub Band.

Album: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Released: 1 June 1967

Recorded: 17, 20 February, 28, 29, 31 March 1967

Genre: Psychedelic rock, experimental rock

Length: 2:37

Label: Parlophone

Writer: Lennon/McCartney

Producer: George Martin

Wikipedia

Inspiration

Lennon wrote the song taking inspiration from a nineteenth century circus poster for Pablo Fanque's circus which he purchased in an antique shop on 31 January 1967 while filming the promotional video for the song "Strawberry Fields Forever" in Kent. Mr. Kite is believed to be William Kite, who worked for Pablo Fanque from 1843 to 1845.

Recording

One of the most musically complex songs on Sgt. Pepper, it was recorded on 17 February 1967 with overdubs on 20 February (organ sound effects), 28 March (harmonica, organ, guitar), 29 March (more organ sound effects), and 31 March. Lennon wanted the track to have a "carnival atmosphere," and told producer George Martin that he wanted "to smell the sawdust on the floor." In the middle eight bars, multiple recordings of fairground organs and calliope music were spliced together to attempt to produce this request; after a great deal of unsuccessful experimentation, George Martin instructed Geoff Emerick to chop the tape into pieces with scissors, throw them up in the air, and re-assemble them at random.

On 17 February, Lennon sings "For the benefit of Mr. Kite" in a joke accent, just before Emerick announces, "For the Benefit of Mr. Kite!, this is take 1." Lennon immediately responds, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" reinforcing his title preference, a phrase lifted intact from the original poster. The exchange is recorded in The Beatles Recording Sessions (slightly misquoted) and audible on track 8 of disc 2 of Anthology 2.

Although Lennon once said of the song that he "wasn't proud of that" and "I was just going through the motions," in 1980 he described it as "pure, like a painting, a pure watercolour."

It was one of three songs from the Sgt. Pepper album that was banned from playing on the BBC, supposedly because the phrase "Henry the Horse" combined two words that were individually known as slang for heroin. Lennon denied that the song had anything to do with heroin.

Personnel

* John Lennon: double-tracked lead vocals and harmony vocals; Hammond organ and piano; tape loops and harmonica.

* Paul McCartney: acoustic guitar and bass.

* George Harrison: harmonica and tambourine.

* Ringo Starr: drums and harmonica.

* George Martin: harmonium, Lowry organ, glockenspiel and tape loops.

* Mal Evans: harmonica.

* Neil Aspinall: harmonica.

* Geoff Emerick: tape loops.

Covers and influence

* The song is performed by The Bee Gees and George Burns in the 1978 film Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

* Serbian new wave band Električni Orgazam recorded a version on their 1983 cover album Les Chansones Populaires.

* Scottish comedian Billy Connolly recorded a mostly spoken-word recording of the song for the George Martin compilation In My Life.

* In 2004 Branimir Krstic released a classical guitar version of the song on the first full classical cover album of Sgt. Pepper.

* In the film Across the Universe, Eddie Izzard appears in a cameo and does a cover of the song in a spoken form.

* Avant-garde band The Residents performed a cover of the song at a 40th Anniversary celebration of Sgt. Pepper with the London Sinfonietta.

* Les Fradkin has an instrumental cover in his 2007 release "Pepper Front To Back."

* Swedish metal band Mister Kite take their name from the song title.

* Reggae band Easy Star All-Stars covered the song in the album Easy Star's Lonely Hearts Dub Band.

Album: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Released: 1 June 1967

Recorded: 17, 20 February, 28, 29, 31 March 1967

Genre: Psychedelic rock, experimental rock

Length: 2:37

Label: Parlophone

Writer: Lennon/McCartney

Producer: George Martin

Wikipedia

Thursday, November 05, 2009

Beatles News

- BlueBeat Ignores EMI, Still Sells Beatles Catalog Online (PC World)

- Beatles star's son James McCartney makes US debut in Fairfield (DesMoinesRegister.com)

- OKC Philharmonic going on a Classical Mystery Tour, giving away Beatles box set (NewsOK.com)

- EMI Sues bluebeat Over Beatles mp3s (PC Magazine)

- Get The Beatles: Rock Band for $99.99 shipped (CNET News)

- Former Beatles drummer in India (Hindustan Times)

- Beatles Remasters Heading to USB (ABC News)

- The Week In Video Game Criticism: The Beatles, Torchlight, Prince Of Persia (Gamasutra)

- Duo Sid n Susie tap into their musical memories (Baltimore Sun)

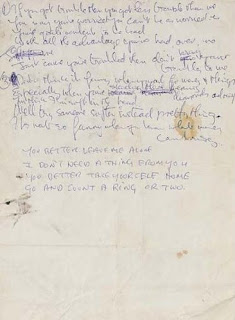

"Tuesday" Lyrics

by Paul McCartney

Original Manuscript (1968?)

Original Manuscript (1968?)

Everything is coming up Tuesday

The coat that I sent to be cleaned

The shoes that went to the cobblers

Are coming back soled & heeled.

Funny thing happened last Friday

I dreamt I was walking with you

In a world that was painted all silver

I walked around town with no shoes

The streets were all smartly coloured

But of course it might be true

The grocercalls on a is calling on Thursday

In streets that were smartly coloured

I pay all my bills on a Friday

When I take a trip out of town

I know that every I go

I hope that I always find

Someone like you who'll have will love me

and always have me on their mind

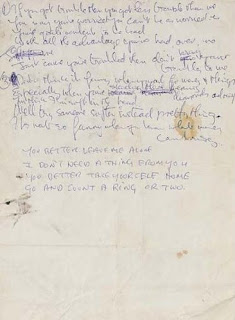

Original Manuscript (1968?)

Original Manuscript (1968?)Everything is coming up Tuesday

The coat that I sent to be cleaned

The shoes that went to the cobblers

Are coming back soled & heeled.

Funny thing happened last Friday

In a world that was painted all silver

I walked around town with no shoes

The streets were all smartly coloured

The grocer

In streets that were smartly coloured

I pay all my bills on a Friday

When I take a trip out of town

I hope that I always find

Someone like you who

and always have me on their mind

Fats Domino

Antoine Dominique "Fats" Domino (born February 26, 1928 in New Orleans, Louisiana) is a classic R&B and rock and roll pianist and singer-songwriter.

Antoine Dominique "Fats" Domino (born February 26, 1928 in New Orleans, Louisiana) is a classic R&B and rock and roll pianist and singer-songwriter.Imperial Records era (1949-1962)

Domino first attracted national attention with "The Fat Man" in 1949 on Imperial Records. This song is an early rock and roll record, featuring a rolling piano and Domino doing "wah-wah" vocalizing over a fat back beat. It sold over a million copies and is widely regarded as the first rock and roll record to do so.

Fats Domino then released a series of hit songs with producer and co-writer Dave Bartholomew, saxophonists Herbert Hardesty and Alvin "Red" Tyler and drummer Earl Palmer. Other notable and long-standing musicians in Domino's band were saxophonists Reggie Houston, Lee Allen, and Fred Kemp, who was also Domino's trusted bandleader. Domino finally crossed into the pop mainstream with "Ain't That a Shame" (1955), which hit the Top Ten, though Pat Boone characteristically hit #1 with a milder cover of the song that received wider radio airplay in a racially-segregated era. Domino would eventually release 37 Top 40 singles, "Whole Lotta Loving" and "Blue Monday" among them.

Domino's first album, Carry on Rockin', was released under the Imperial imprint, #9009, in November 1955 and subsequently reissued as Rock and Rollin' with Fats Domino in 1956. Combining a number of his hits along with some tracks which had not yet been released as singles, the album went on under its alternate title to reach #17 on the "Pop Albums" chart.

His 1956 up tempo version of the 1940 Bobby Cerdeira, Al Lewis & Larry Stock song, "Blueberry Hill" reached #2 in the Top 40, was #1 on the R&B charts for 11 weeks, and was his biggest hit. "Blueberry Hill" sold more than 5 million copies worldwide in 1956-57. The song had earlier been recorded by Gene Autry, and Louis Armstrong among many others. He also hit singles between 1956-1959, including "When My Dreamboat Comes Along" (Pop #14), "I'm Walkin'" (Pop #4), "Valley of Tears" (Pop #8), "It's You I Love" (Pop #6), "Whole Lotta Loving" (Pop #6), "I Want to Walk You Home" (Pop #8), and "Be My Guest" (Pop #8).

Fats appeared in two films released in 1956: Shake, Rattle & Rock! and The Girl Can't Help It. On December 18, 1957, Domino's hit "The Big Beat" was featured on Dick Clark's American Bandstand.

Domino continued to have a steady series of hits for Imperial through early 1962, including "Walkin' to New Orleans" (1960) (Pop #6) co-written by Bobby Charles and "My Girl, Josephine" (Pop #14) from the same year. After Imperial Records was sold to outside interests in early 1963, Domino left the label: "I stuck with them until they sold out", he claimed in 1979. In all, Domino recorded over 60 singles for the label, placing 40 songs in the top 10 on the R&B charts, and scoring 11 top 10 singles on the pop charts. Twenty-two of Domino's Imperial singles were double-sided hits.

Post-Imperial recording career (1963-1970s)

Domino moved to ABC-Paramount Records in,1963 where the label dictated that he would record in Nashville rather than New Orleans. He was assigned a new producer (Felton Jarvis) and a new arranger (Bill Justis) -- Domino's long-term collaboration with producer/arranger/frequent co-writer Dave Bartholomew, who oversaw virtually all of his Imperial hits, was seemingly at an end.

Jarvis and Justis changed the Domino sound somewhat, notably by adding the backing of a countrypolitan-style vocal chorus to most of his new recordings. Perhaps as a result of this tinkering with an established formula, Domino's chart career was drastically curtailed. He released 11 singles for ABC-Paramount, but only had one top 40 entry with "Red Sails In The Sunset" (1963). By the end of 1964 the British Invasion had changed the tastes of the record-buying public, and Domino's chart run was over.

Despite the lack of chart success, Domino continued to record steadily until about 1970, leaving ABC-Paramount in mid-1965 and recording for a variety of other labels (Mercury, Bartholomew's small Broadmoor label reuniting with Dave Bartholomew along the way, and Reprise). He also continued as a popular live act for several decades.

He was acknowledged as an important influence on the music of the 1960s and 1970s by some of the top artists of that era. Paul McCartney reportedly wrote the Beatles song "Lady Madonna" in an emulation of Domino's style, combining it with a nod to Humphrey Lyttelton's 1956 hit "Bad Penny Blues", a record which Joe Meek had engineered. Domino did manage to return to the "Hot 100" charts one final time in 1968—with his own recording of "Lady Madonna". That recording, as well as covers of two other Beatles songs, appeared on his Reprise LP Fats Is Back. Both John Lennon and Paul McCartney later recorded Fats Domino songs.

Later career (1980s-2005)

In the 1980s, Domino decided he would no longer leave New Orleans, having a comfortable income from royalties and a dislike for touring, and claiming he could not get any food that he liked any place else. His induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and an invitation to perform at the White House failed to persuade Domino to make an exception to this policy.

Fats Domino was persuaded to perform out of town periodically for Dianna Chenevert, agent, founder and president of New Orleans based Omni Attractions, during the 1980s and early 1990s. Most of these engagements were in and around New Orleans, but also included a concert in Texas at West End Market Place in downtown Dallas on October 24, 1986.

On October 12, 1983 USA Today reported that Domino was included in Chenevert's "Southern Stars" promotional poster for the agency (along with historically preserving childhood photographs of other famous living musicians from New Orleans and Louisiana on it). Fats provided a photograph of his first recording session, which was the only one he had left from his childhood. Domino autographed these posters, whose recipients included USA Today's Gannett president Al Newharth, and Peter Morton founder of the Hard Rock Cafe. Times-Picayune columnist Betty Guillaud noted on September 30, 1987 that Domino also provided Chenevert with an autographed pair of his shoes (and signed a black grand piano lid) for the Hard Rock location in New Orleans.

Domino lived in a mansion in a predominantly working-class Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood, where he was a familiar sight in his bright pink Cadillac. He makes yearly appearances at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival and other local events. Domino was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987. In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked him #25 on their list of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time."

Domino and Hurricane Katrina

When Hurricane Katrina was approaching New Orleans in August 2005, Dianna Chenevert encouraged Fats to evacuate, but he chose to stay at home with his family, partly because of his wife's poor health. Unfortunately his house was in an area that was heavily flooded. Chenevert e-mailed writers at the Times Picayune newspaper and the Coast Guard with the Dominos' location.

Someone thought Fats was dead, and spray-painted a message on his home, "RIP Fats. You will be missed", which was shown in news photos. On September 1, Domino's agent, Al Embry, announced that he had not heard from the musician since before the hurricane had struck.

Later that day, CNN reported that Domino was rescued by a Coast Guard helicopter. Embry confirmed that Domino and his family had been rescued. The Domino family was then taken to a Baton Rouge shelter, after which they were picked up by JaMarcus Russell, the starting quarterback of the Louisiana State University football team, and Fats' granddaughter's boyfriend. He let the Dominoes stay in his apartment. The Washington Post reported that on September 2, they had left Russell's apartment after sleeping three nights on the couch. "We've lost everything," Domino said, according to the Post.

By January 2006, work to gut and repair Domino's home and office had begun. For the meantime, the Domino family is residing in Harvey, Louisiana.

Chenevert replaced the Southern Stars poster Fats Domino lost in Katrina and President George W. Bush also made a personal visit and replaced the medal that President Bill Clinton had previously awarded Fats.

Post-Katrina activity

Domino was the first artist to be announced as scheduled to perform at the 2006 Jazz & Heritage Festival. However, he was too ill to perform when scheduled and was only able to offer the audience an on-stage greeting. Domino also released an album Alive and Kickin' in early 2006 to benefit the Tipitina's Foundation, which supports indigent local musicians. The title song was recorded after Katrina, but most of the cuts were from unreleased sessions in the 1990s.

On January 12, 2007, Domino was honored with OffBeat magazine's Lifetime Achievement Award at the annual Best of the Beat Awards held at House of Blues in New Orleans. New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin declared the day "Fats Domino Day in New Orleans" and presented Fats Domino with a signed declaration. OffBeat publisher Jan Ramsey and WWL-TV's Eric Paulsen presented Fats Domino with the Lifetime Achievement Award. An all-star musical tribute followed with an introduction by the legendary producer Cosimo Matassa. The Lil' Band O' Gold rhythm section, Warren Storm, Kenny Bill Stinson, David Egan and C.C. Adcock, not only anchored the band, but each contributed lead vocals, swamp pop legend Warren Storm leading off with "Let the Four Winds Blow" and "The Prisoner Song", which he proudly introduced by saying, "Fats Domino recorded this in 1958.. and so did I." The horn section included Lil' Band O' Gold's Dickie Landry, the Iguanas' Derek Huston, and long-time Domino horn men Roger Lewis, Elliot "Stackman" Callier and Herb Hardesty. They were joined by Jon Cleary (who also played guitar in the rhythm section), Al "Carnival Time" Johnson, Irma Thomas, George Porter, Jr. (who, naturally, came up with a funky arrangement for "You Keep On Knocking"), Art Neville, Dr. John and Allen Toussaint, who wrote and debuted a song in tribute of Domino for the occasion. Though Domino didn't perform, those near him recall him playing air piano and singing along to his own songs.

Fats Domino returned to stage on May 19, 2007, at Tipitina's at New Orleans, performing to a full house. A foundation has been formed and a show is being planned for Domino and the restoration of his home, where he intends to return someday. "I like it down there" he said in a February, 2006 CBS News interview.

In September 2007, Domino was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall Of Fame. He has also been inducted into the Delta Music Museum Hall of Fame in Ferriday.

In December 2007, Fats Domino was inducted into the Hit Parade Hall of Fame.

Wikipedia

John Lennon: 1980

By David Sheff / September 8-28, 1980

PLAYBOY: The album obviously reflects your new priorities. How have things gone for you since you made that decision?

LENNON: We got back together, decided this was our life, that having a baby was important to us and that anything else was subsidiary to that. We worked hard for that child. We went through all hell trying to have a baby, through many miscarriages and other problems. He is what they call a love child in truth. Doctors told us we could never have a child. We almost gave up. "Well, that's it, then, we can't have one. . . ." We were told something was wrong with my sperm, that I abused myself so much in my youth that there was no chance. Yoko was 43, and so they said, no way. She has had too many miscarriages and when she was a young girl, there were no pills, so there were lots of abortions and miscarriages; her stomach must be like Kew Gardens in London. No way. But this Chinese acupuncturist in San Francisco said, "You behave yourself. No drugs, eat well, no drink. You have child in 18 months." And we said, "But the English doctors said. . . ." He said, "Forget what they said. You have child." We had Sean and sent the acupuncturist a Polaroid of him just before he died, God rest his soul.

PLAYBOY: Were there any problems because of Yoko's age?

LENNON: Not because of her age but because of a screw- up in the hospital and the fucking price of fame. Somebody had made a transfusion of the wrong blood type into Yoko. I was there when it happened, and she starts to go rigid, and then shake, from the pain and the trauma. I run up to this nurse and say, "Go get the doctor!" I'm holding on tight to Yoko while this guy gets to the hospital room. He walks in, hardly notices that Yoko is going through fucking convulsions, goes straight for me, smiles, shakes my hand and says, "I've always wanted to meet you, Mr. Lennon, I always enjoyed your music." I start screaming: "My wife's dying and you wanna talk about my music!" Christ!

PLAYBOY: Now that Sean is almost five, is he conscious of the fact that his father was a Beatle or have you protected him from your fame?

LENNON: I haven't said anything. Beatles were never mentioned to him. There was no reason to mention it; we never played Beatle records around the house, unlike the story that went around that I was sitting in the kitchen for the past five years, playing Beatle records and reliving my past like some kind of Howard Hughes. He did see "Yellow Submarine" at a friend's, so I had to explain what a cartoon of me was doing in a movie.

PLAYBOY: Does he have an awareness of the Beatles?

LENNON: He doesn't differentiate between the Beatles and Daddy and Mommy. He thinks Yoko was a Beatle, too. I don't have Beatle records on the jukebox he listens to. He's more exposed to early rock 'n' roll. He's into "Hound Dog." He thinks it's about hunting. Sean's not going to public school, by the way. We feel he can learn the three Rs when he wants to -- or when the law says he has to, I suppose. I'm not going to fight it. Otherwise, there's no reason for him to be learning to sit still. I can't see any reason for it. Sean now has plenty of child companionship, which everybody says is important, but he also is with adults a lot. He's adjusted to both. The reason why kids are crazy is because nobody can face the responsibility of bringing them up. Everybody's too scared to deal with children all the time, so we reject them and send them away and torture them. The ones who survive are the conformists -- their bodies are cut to the size of the suits -- the ones we label good. The ones who don't fit the suits either are put in mental homes or become artists.

PLAYBOY: Your son, Julian, from your first marriage must be in his teens. Have you seen him over the years?

LENNON: Well, Cyn got possession, or whatever you call it. I got rights to see him on his holidays and all that business, and at least there's an open line still going. It's not the best relationship between father and son, but it is there. He's 17 now. Julian and I will have a relationship in the future. Over the years, he's been able to see through the Beatle image and to see through the image that his mother will have given him, subconsciously or consciously. He's interested in girls and autobikes now. I'm just sort of a figure in the sky, but he's obliged to communicate with me, even when he probably doesn't want to.

PLAYBOY: You're being very honest about your feelings toward him to the point of saying that Sean is your first child. Are you concerned about hurting him?

LENNON: I'm not going to lie to Julian. Ninety percent of the people on this planet, especially in the West, were born out of a bottle of whiskey on a Saturday night, and there was no intent to have children. So 90 percent of us -- that includes everybody -- were accidents. I don't know anybody who was a planned child. All of us were Saturday-night specials. Julian is in the majority, along with me and everybody else. Sean is a planned child, and therein lies the difference. I don't love Julian any less as a child. He's still my son, whether he came from a bottle of whiskey or because they didn't have pills in those days. He's here, he belongs to me and he always will.

PLAYBOY: Yoko, your relationship with your daughter has been much rockier.

ONO: I lost Kyoko when she was about five. I was sort of an offbeat mother, but we had very good communication. I wasn't particularly taking care of her, but she was always with me -- onstage or at gallery shows, whatever. When she was not even a year old, I took her onstage as an instrument -- an uncontrollable instrument, you know. My communication with her was on the level of sharing conversation and doing things. She was closer to my ex-husband because of that.

PLAYBOY: What happened when she was five?

ONO: John and I got together and I separated from my ex- husband [Tony Cox]. He took Kyoko away. It became a case of parent kidnapping and we tried to get her back.

LENNON: It was a classic case of men being macho. It turned into me and Allen Klein trying to dominate Tony Cox. Tony's attitude was, "You got my wife, but you won't get my child." In this battle, Yoko and the child were absolutely forgotten. I've always felt bad about it. It became a case of the shoot-out at the O.K. Corral: Cox fled to the hills and hid out and the sheriff and I tracked him down. First we won custody in court. Yoko didn't want to go to court, but the men, Klein and I, did it anyway.

ONO: Allen called up one day, saying I won the court case. He gave me a piece of paper. I said, "What is this piece of paper? Is this what I won? I don't have my child." I knew that taking them to court would frighten them and, of course, it did frighten them. So Tony vanished. He was very strong, thinking that the capitalists, with their money and lawyers and detectives, were pursuing him. It made him stronger.

LENNON: We chased him all over the world. God knows where he went. So if you're reading this, Tony, let's grow up about it. It's gone. We don't want to chase you anymore, because we've done enough damage.

ONO: We also had private detectives chasing Kyoko, which I thought was a bad trip, too. One guy came to report, "It was great! We almost had them. We were just behind them in a car, but they sped up and got away." I went hysterical. "What do you mean you almost got them? We are talking about my child!"

LENNON: It was like we were after an escaped convict.

PLAYBOY: Were you so persistent because you felt you were better for Kyoko?

LENNON: Yoko got steamed into a guilt thing that if she wasn't attacking them with detectives and police and the FBI, then she wasn't a good mother looking for her baby. She kept saying, "Leave them alone, leave them alone," but they said you can't do that.

ONO: For me, it was like they just disappeared from my life. Part of me left with them.

PLAYBOY: How old is she now?

ONO: Seventeen, the same as John's son.

PLAYBOY: Perhaps when she gets older, she'll seek you out.

ONO: She is totally frightened. There was a time in Spain when a lawyer and John thought that we should kidnap her.

LENNON: [Sighing] I was just going to commit hara-kiri first.

ONO: And we did kidnap her and went to court. The court did a very sensible thing -- the judge took her into a room and asked her which one of us she wanted to go with. Of course, she said Tony. We had scared her to death. So now she must be afraid that if she comes to see me, she'll never see her father again.

LENNON: When she gets to be in her 20s, she'll understand that we were idiots and we know we were idiots. She might give us a chance.

ONO: I probably would have lost Kyoko even if it wasn't for John. If I had separated from Tony, there would have been some difficulty.

LENNON: I'll just half-kill myself.

ONO: [To John] Part of the reason things got so bad was because with Kyoko, it was you and Tony dealing. Men. With your son Julian, it was women -- there was more understanding between me and Cyn.

PLAYBOY: Can you explain that?

ONO: For example, there was a birthday party that Kyoko had and we were both invited, but John felt very uptight about it and he didn't go. He wouldn't deal with Tony. But we were both invited to Julian's party and we both went.

LENNON: Oh, God, it's all coming out.

ONO: Or like when I was invited to Tony's place alone, I couldn't go; but when John was invited to Cyn's, he did go.

LENNON: One rule for the men, one for the women.

ONO: So it was easier for Julian, because I was allowing it to happen.

LENNON: But I've said a million Hail Marys. What the hell else can I do?

PLAYBOY: Yoko, after this experience, how do you feel about leaving Sean's rearing to John?

ONO: I am very clear about my emotions in that area. I don't feel guilty. I am doing it in my own way. It may not be the same as other mothers, but I'm doing it the way I can do it. In general, mothers have a very strong resentment toward their children, even though there's this whole adulation about motherhood and how mothers really think about their children and how they really love them. I mean, they do, but it is not humanly possible to retain emotion that mothers are supposed to have within this society. Women are just too stretched out in different directions to retain that emotion. Too much is required of them. So I say to John----

LENNON: I am her favorite husband----

ONO: "I am carrying the baby nine months and that is enough, so you take care of it afterward." It did sound like a crude remark, but I really believe that children belong to the society. If a mother carries the child and a father raises it, the responsibility is shared.

PLAYBOY: Did you resent having to take so much responsibility, John?

LENNON: Well, sometimes, you know, she'd come home and say, "I'm tired." I'd say, only partly tongue in cheek, "What the fuck do you think I am? I'm 24 hours with the baby! Do you think that's easy?" I'd say, "You're going to take some more interest in the child." I don't care whether it's a father or a mother. When I'm going on about pimples and bones and which TV shows to let him watch, I would say, "Listen, this is important. I don't want to hear about your $20,000,000 deal tonight!" [To Yoko] I would like both parents to take care of the children, but how is a different matter.

ONO: Society should be more supportive and understanding.

LENNON: It's true. The saying "You've come a long way, baby" applies more to me than to her. As Harry Nilsson says, "Everything is the opposite of what it is, isn't it?" It's men who've come a long way from even contemplating the idea of equality. But although there is this thing called the women's movement, society just took a laxative and they've just farted. They haven't really had a good shit yet. The seed was planted sometime in the late Sixties, right? But the real changes are coming. I am the one who has come a long way. I was the pig. And it is a relief not to be a pig. The pressures of being a pig were enormous. I don't have any hankering to be looked upon as a sex object, a male, macho rock-'n'-roll singer. I got over that a long time ago. I'm not even interested in projecting that. So I like it to be known that, yes, I looked after the baby and I made bread and I was a househusband and I am proud of it. It's the wave of the future and I'm glad to be in on the forefront of that, too.

ONO: So maybe both of us learned a lot about how men and women suffer because of the social structure. And the only way to change it is to be aware of it. It sounds simple, but important things are simple.

PLAYBOY: John, does it take actually reversing roles with women to understand?

LENNON: It did for this man. But don't forget, I'm the one who benefited the most from doing it. Now I can step back and say Sean is going to be five years old and I was able to spend his first five years with him and I am very proud of that. And come to think of it, it looks like I'm going to be 40 and life begins at 40 -- so they promise. And I believe it, too. I feel fine and I'm very excited. It's like, you know, hitting 21, like, "Wow, what's going to happen next?" Only this time we're together.

ONO: If two are gathered together, there's nothing you can't do.

PLAYBOY: What does the title of your new album, "Double Fantasy," mean?

LENNON: It's a flower, a type of freesia, but what it means to us is that if two people picture the same image at the same time, that is the secret. You can be together but projecting two different images and either whoever's the stronger at the time will get his or her fantasy fulfilled or you will get nothing but mishmash.

PLAYBOY: You saw the news item that said you were putting your sex fantasies out as an album.

LENNON: Oh, yeah. That is like when we did the bed-in in Toronto in 1969. They all came charging through the door, thinking we were going to be screwing in bed. Of course, we were just sitting there with peace signs.

PLAYBOY: What was that famous bed-in all about?

LENNON: Our life is our art. That's what the bed-ins were. When we got married, we knew our honeymoon was going to be public, anyway, so we decided to use it to make a statement. We sat in bed and talked to reporters for seven days. It was hilarious. In effect, we were doing a commercial for peace on the front page of the papers instead of a commercial for war.

PLAYBOY: You stayed in bed and talked about peace?

LENNON: Yes. We answered questions. One guy kept going over the point about Hitler: "What do you do about Fascists? How can you have peace when you've got a Hitler?" Yoko said, "I would have gone to bed with him." She said she'd have needed only ten days with him. People loved that one.

ONO: I said it facetiously, of course. But the point is, you're not going to change the world by fighting. Maybe I was naive about the ten days with Hitler. After all, it took 13 years with John Lennon. [She giggles]

PLAYBOY: What were the reports about your making love in a bag?

ONO: We never made love in a bag. People probably imagined that we were making love. It was just, all of us are in a bag, you know. The point was the outline of the bag, you know, the movement of the bag, how much we see of a person, you know. But, inside, there might be a lot going on. Or maybe nothing's going on.

PLAYBOY: Briefly, what about the statement on the new album?

LENNON: Very briefly, it's about very ordinary things between two people. The lyrics are direct. Simple and straight. I went through my Dylanesque period a long time ago with songs like "I am the Walrus:" the trick of never saying what you mean but giving the impression of something more. Where more or less can be read into it. It's a good game.

PLAYBOY: What are your musical preferences these days?

LENNON: Well, I like all music, depending on what time of day it is. I don't like styles of music or people per se. I can't say I enjoy the Pretenders, but I like their hit record. I enjoy the B-52s, because I heard them doing Yoko. It's great. If Yoko ever goes back to her old sound, they'll be saying, "Yeah, she's copying the B-52s."

ONO: We were doing a lot of the punk stuff a long time ago.

PLAYBOY: Lennon and Ono, the original punks.

ONO: You're right.

PLAYBOY: John, what's your opinion of the newer waves?

LENNON: I love all this punky stuff. It's pure. I'm not, however, crazy about the people who destroy themselves.

PLAYBOY: You disagree with Neil Young's lyric in "Rust Never Sleeps" -- "It's better to burn out than to fade away...."

LENNON: I hate it. It's better to fade away like an old soldier than to burn out. I don't appreciate worship of dead Sid Vicious or of dead James Dean or of dead John Wayne. It's the same thing. Making Sid Vicious a hero, Jim Morrison -- it's garbage to me. I worship the people who survive. Gloria Swanson, Greta Garbo. They're saying John Wayne conquered cancer -- he whipped it like a man. You know, I'm sorry that he died and all that -- I'm sorry for his family -- but he didn't whip cancer. It whipped him. I don't want Sean worshiping John Wayne or Sid Vicious. What do they teach you? Nothing. Death. Sid Vicious died for what? So that we might rock? I mean, it's garbage, you know. If Neil Young admires that sentiment so much, why doesn't he do it? Because he sure as hell faded away and came back many times, like all of us. No, thank you. I'll take the living and the healthy.

PLAYBOY: Do you listen to the radio?

LENNON: Muzak or classical. I don't purchase records. I do enjoy listening to things like Japanese folk music or Indian music. My tastes are very broad. When I was a housewife, I just had Muzak on -- background music -- 'cause it relaxes you.

PLAYBOY: Yoko?

ONO: No.

PLAYBOY: Do you go out and buy records?

ONO: Or read the newspaper or magazines or watch TV? No.

PLAYBOY: The inevitable question, John. Do you listen to your records?

LENNON: Least of all my own.

PLAYBOY: Even your classics?

LENNON: Are you kidding? For pleasure, I would never listen to them. When I hear them, I just think of the session -- it's like an actor watching himself in an old movie. When I hear a song, I remember the Abbey Road studio, the session, who fought with whom, where I was sitting, banging the tambourine in the corner----

ONO: In fact, we really don't enjoy listening to other people's work much. We sort of analyze everything we hear.

PLAYBOY: Yoko, were you a Beatles fan?

ONO: No. Now I notice the songs, of course. In a restaurant, John will point out, "Ahh, they're playing George" or something.

PLAYBOY: John, do you ever go out to hear music?

LENNON: No, I'm not interested. I'm not a fan, you see. I might like Jerry Lee Lewis singing "A Whole Lot a Shakin'" on the record, but I'm not interested in seeing him perform it.

PLAYBOY: Your songs are performed more than most other songwriters'. How does that feel?

LENNON: I'm always proud and pleased when people do my songs. It gives me pleasure that they even attempt them, because a lot of my songs aren't that doable. I go to restaurants and the groups always play "Yesterday." I even signed a guy's violin in Spain after he played us "Yesterday." He couldn't understand that I didn't write the song. But I guess he couldn't have gone from table to table playing "I am the Walrus."

PLAYBOY: How does it feel to have influenced so many people?

LENNON: It wasn't really me or us. It was the times. It happened to me when I heard rock 'n' roll in the Fifties. I had no idea about doing music as a way of life until rock 'n' roll hit me.

PLAYBOY: Do you recall what specifically hit you?

LENNON: It was "Rock Around the Clock," I think. I enjoyed Bill Haley, but I wasn't overwhelmed by him. It wasn't until "Heartbreak Hotel" that I really got into it.

ONO: I am sure there are people whose lives were affected because they heard Indian music or Mozart or Bach. More than anything, it was the time and the place when the Beatles came up. Something did happen there. It was a kind of chemical. It was as if several people gathered around a table and a ghost appeared. It was that kind of communication. So they were like mediums, in a way. It's not something you can force. It was the people, the time, their youth and enthusiasm.

PLAYBOY: For the sake of argument, we'll maintain that no other contemporary artist or group of artists moved as many people in such a profound way as the Beatles.

LENNON: But what moved the Beatles?

PLAYBOY: You tell us.

LENNON: All right. Whatever wind was blowing at the time moved the Beatles, too. I'm not saying we weren't flags on the top of a ship; but the whole boat was moving. Maybe the Beatles were in the crow's-nest, shouting, "Land ho," or something like that, but we were all in the same damn boat.

ONO: The Beatles themselves were a social phenomenon not that aware of what they were doing. In a way----

LENNON: [Under his breath] This Beatles talk bores me to death.

ONO: As I said, they were like mediums. They weren't conscious of all they were saying, but it was coming through them.

PLAYBOY: Why?

LENNON: We tuned in to the message. That's all. I don't mean to belittle the Beatles when I say they weren't this, they weren't that. I'm just trying not to overblow their importance as separate from society. And I don't think they were more important than Glenn Miller or Woody Herman or Bessie Smith. It was our generation, that's all. It was Sixties music.

PLAYBOY: What do you say to those who insist that all rock since the Beatles has been the Beatles redone?

LENNON: All music is rehash. There are only a few notes. Just variations on a theme. Try to tell the kids in the Seventies who were screaming to the Bee Gees that their music was just the Beatles redone. There is nothing wrong with the Bee Gees. They do a damn good job. There was nothing else going on then.

PLAYBOY: Wasn't a lot of the Beatles' music at least more intelligent?

LENNON: The Beatles were more intellectual, so they appealed on that level, too. But the basic appeal of the Beatles was not their intelligence. It was their music. It was only after some guy in the "London Times" said there were Aeolian cadences in "It Won't Be Long" that the middle classes started listening to it -- because somebody put a tag on it.

PLAYBOY: Did you put Aeolian cadences in "It Won't Be Long?"

LENNON: To this day, I don't have any idea what they are. They sound like exotic birds.

PLAYBOY: How did you react to the misinterpretations of your songs?

LENNON: For instance?

PLAYBOY: The most obvious is the "Paul is dead" fiasco. You already explained the line in "Glass Onion." What about the line in "I am the Walrus" - - "I buried Paul"?

LENNON: I said "Cranberry sauce." That's all I said. Some people like ping-pong, other people like digging over graves. Some people will do anything rather than be here now.

PLAYBOY: What about the chant at the end of the song: "Smoke pot, smoke pot, everybody smoke pot"?

LENNON: No, no, no. I had this whole choir saying, "Everybody's got one, everybody's got one." But when you get 30 people, male and female, on top of 30 cellos and on top of the Beatles' rock-'n'-roll rhythm section, you can't hear what they're saying.

PLAYBOY: What does "everybody got"?

LENNON: Anything. You name it. One penis, one vagina, one asshole -- you name it.

PLAYBOY: Did it trouble you when the interpretations of your songs were destructive, such as when Charles Manson claimed that your lyrics were messages to him?

LENNON: No. It has nothing to do with me. It's like that guy, Son of Sam, who was having these talks with the dog. Manson was just an extreme version of the people who came up with the "Paul is dead" thing or who figured out that the initials to "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" were LSD and concluded I was writing about acid.

PLAYBOY: Where did "Lucy in the Sky" come from?

LENNON: My son Julian came in one day with a picture he painted about a school friend of his named Lucy. He had sketched in some stars in the sky and called it "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds," Simple.

PLAYBOY: The other images in the song weren't drug-inspired?

LENNON: The images were from "Alice in Wonderland." It was Alice in the boat. She is buying an egg and it turns into Humpty Dumpty. The woman serving in the shop turns into a sheep and the next minute they are rowing in a rowing boat somewhere and I was visualizing that. There was also the image of the female who would someday come save me -- a "girl with kaleidoscope eyes" who would come out of the sky. It turned out to be Yoko, though I hadn't met Yoko yet. So maybe it should be "Yoko in the Sky with Diamonds."

PLAYBOY: Do you have any interest in the pop historians analyzing the Beatles as a cultural phenomenon?

LENNON: It's all equally irrelevant. Mine is to do and other people's is to record, I suppose. Does it matter how many drugs were in Elvis' body? I mean, Brian Epstein's sex life will make a nice "Hollywood Babylon" someday, but it is irrelevant.

PLAYBOY: What started the rumors about you and Epstein?

LENNON: I went on holiday to Spain with Brian -- which started all the rumors that he and I were having a love affair. Well, it was almost a love affair, but not quite. It was never consummated. But we did have a pretty intense relationship. And it was my first experience with someone I knew was a homosexual. He admitted it to me. We had this holiday together because Cyn was pregnant and we left her with the baby and went to Spain. Lots of funny stories, you know. We used to sit in cafs and Brian would look at all the boys and I would ask, "Do you like that one? Do you like this one?" It was just the combination of our closeness and the trip that started the rumors.

PLAYBOY: It's interesting to hear you talk about your old songs such as "Lucy in the Sky" and "Glass Onion." Will you give some brief thoughts on some of our favorites?

LENNON: Right.

PLAYBOY: Let's start with "In My Life."

LENNON: It was the first song I wrote that was consciously about my life. [Sings] "There are places I'll remember/all my life though some have changed. . . ." Before, we were just writing songs a la Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly -- pop songs with no more thought to them than that. The words were almost irrelevant. "In My Life" started out as a bus journey from my house at 250 Menlove Avenue to town, mentioning all the places I could recall. I wrote it all down and it was boring. So I forgot about it and laid back and these lyrics started coming to me about friends and lovers of the past. Paul helped with the middle eight.

PLAYBOY: "Yesterday."

LENNON: Well, we all know about "Yesterday." I have had so much accolade for "Yesterday." That is Paul's song, of course, and Paul's baby. Well done. Beautiful -- and I never wished I had written it.

PLAYBOY: "With a Little Help from My Friends."

LENNON: This is Paul, with a little help from me. "What do you see when you turn out the light/I can't tell you, but I know it's mine ..." is mine.

PLAYBOY: "I am the Walrus."

LENNON: The first line was written on one acid trip one weekend. The second line was written on the next acid trip the next weekend, and it was filled in after I met Yoko. Part of it was putting down Hare Krishna. All these people were going on about Hare Krishna, Allen Ginsberg in particular. The reference to "Element'ry penguin" is the elementary, naive attitude of going around chanting, "Hare Krishna," or putting all your faith in any one idol. I was writing obscurely, a la Dylan, in those days.

PLAYBOY: The song is very complicated, musically.

LENNON: It actually was fantastic in stereo, but you never hear it all. There was too much to get on. It was too messy a mix. One track was live BBC Radio -- Shakespeare or something -- I just fed in whatever lines came in.

PLAYBOY: What about the walrus itself?

LENNON: It's from "The Walrus and the Carpenter." "Alice in Wonderland." To me, it was a beautiful poem. It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist and social system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with the Beatles' work. Later, I went back and looked at it and realized that the walrus was the bad guy in the story and the carpenter was the good guy. I thought, Oh, shit, I picked the wrong guy. I should have said, "I am the carpenter." But that wouldn't have been the same, would it? [Singing] "I am the carpenter...."

PLAYBOY: How about "She Came in Through the Bathroom Window?"

LENNON: That was written by Paul when we were in New York forming Apple, and he first met Linda. Maybe she's the one who came in the window. She must have. I don't know. Somebody came in the window.

PLAYBOY: "I Feel Fine."

LENNON: That's me, including the guitar lick with the first feedback ever recorded. I defy anybody to find an earlier record -- unless it is some old blues record from the Twenties -- with feedback on it.

PLAYBOY: "When I'm Sixty-Four."

LENNON: Paul completely. I would never even dream of writing a song like that. There are some areas I never think about and that is one of them.

PLAYBOY: The album obviously reflects your new priorities. How have things gone for you since you made that decision?

LENNON: We got back together, decided this was our life, that having a baby was important to us and that anything else was subsidiary to that. We worked hard for that child. We went through all hell trying to have a baby, through many miscarriages and other problems. He is what they call a love child in truth. Doctors told us we could never have a child. We almost gave up. "Well, that's it, then, we can't have one. . . ." We were told something was wrong with my sperm, that I abused myself so much in my youth that there was no chance. Yoko was 43, and so they said, no way. She has had too many miscarriages and when she was a young girl, there were no pills, so there were lots of abortions and miscarriages; her stomach must be like Kew Gardens in London. No way. But this Chinese acupuncturist in San Francisco said, "You behave yourself. No drugs, eat well, no drink. You have child in 18 months." And we said, "But the English doctors said. . . ." He said, "Forget what they said. You have child." We had Sean and sent the acupuncturist a Polaroid of him just before he died, God rest his soul.

PLAYBOY: Were there any problems because of Yoko's age?

LENNON: Not because of her age but because of a screw- up in the hospital and the fucking price of fame. Somebody had made a transfusion of the wrong blood type into Yoko. I was there when it happened, and she starts to go rigid, and then shake, from the pain and the trauma. I run up to this nurse and say, "Go get the doctor!" I'm holding on tight to Yoko while this guy gets to the hospital room. He walks in, hardly notices that Yoko is going through fucking convulsions, goes straight for me, smiles, shakes my hand and says, "I've always wanted to meet you, Mr. Lennon, I always enjoyed your music." I start screaming: "My wife's dying and you wanna talk about my music!" Christ!

PLAYBOY: Now that Sean is almost five, is he conscious of the fact that his father was a Beatle or have you protected him from your fame?

LENNON: I haven't said anything. Beatles were never mentioned to him. There was no reason to mention it; we never played Beatle records around the house, unlike the story that went around that I was sitting in the kitchen for the past five years, playing Beatle records and reliving my past like some kind of Howard Hughes. He did see "Yellow Submarine" at a friend's, so I had to explain what a cartoon of me was doing in a movie.

PLAYBOY: Does he have an awareness of the Beatles?

LENNON: He doesn't differentiate between the Beatles and Daddy and Mommy. He thinks Yoko was a Beatle, too. I don't have Beatle records on the jukebox he listens to. He's more exposed to early rock 'n' roll. He's into "Hound Dog." He thinks it's about hunting. Sean's not going to public school, by the way. We feel he can learn the three Rs when he wants to -- or when the law says he has to, I suppose. I'm not going to fight it. Otherwise, there's no reason for him to be learning to sit still. I can't see any reason for it. Sean now has plenty of child companionship, which everybody says is important, but he also is with adults a lot. He's adjusted to both. The reason why kids are crazy is because nobody can face the responsibility of bringing them up. Everybody's too scared to deal with children all the time, so we reject them and send them away and torture them. The ones who survive are the conformists -- their bodies are cut to the size of the suits -- the ones we label good. The ones who don't fit the suits either are put in mental homes or become artists.

PLAYBOY: Your son, Julian, from your first marriage must be in his teens. Have you seen him over the years?

LENNON: Well, Cyn got possession, or whatever you call it. I got rights to see him on his holidays and all that business, and at least there's an open line still going. It's not the best relationship between father and son, but it is there. He's 17 now. Julian and I will have a relationship in the future. Over the years, he's been able to see through the Beatle image and to see through the image that his mother will have given him, subconsciously or consciously. He's interested in girls and autobikes now. I'm just sort of a figure in the sky, but he's obliged to communicate with me, even when he probably doesn't want to.

PLAYBOY: You're being very honest about your feelings toward him to the point of saying that Sean is your first child. Are you concerned about hurting him?

LENNON: I'm not going to lie to Julian. Ninety percent of the people on this planet, especially in the West, were born out of a bottle of whiskey on a Saturday night, and there was no intent to have children. So 90 percent of us -- that includes everybody -- were accidents. I don't know anybody who was a planned child. All of us were Saturday-night specials. Julian is in the majority, along with me and everybody else. Sean is a planned child, and therein lies the difference. I don't love Julian any less as a child. He's still my son, whether he came from a bottle of whiskey or because they didn't have pills in those days. He's here, he belongs to me and he always will.

PLAYBOY: Yoko, your relationship with your daughter has been much rockier.

ONO: I lost Kyoko when she was about five. I was sort of an offbeat mother, but we had very good communication. I wasn't particularly taking care of her, but she was always with me -- onstage or at gallery shows, whatever. When she was not even a year old, I took her onstage as an instrument -- an uncontrollable instrument, you know. My communication with her was on the level of sharing conversation and doing things. She was closer to my ex-husband because of that.

PLAYBOY: What happened when she was five?

ONO: John and I got together and I separated from my ex- husband [Tony Cox]. He took Kyoko away. It became a case of parent kidnapping and we tried to get her back.

LENNON: It was a classic case of men being macho. It turned into me and Allen Klein trying to dominate Tony Cox. Tony's attitude was, "You got my wife, but you won't get my child." In this battle, Yoko and the child were absolutely forgotten. I've always felt bad about it. It became a case of the shoot-out at the O.K. Corral: Cox fled to the hills and hid out and the sheriff and I tracked him down. First we won custody in court. Yoko didn't want to go to court, but the men, Klein and I, did it anyway.

ONO: Allen called up one day, saying I won the court case. He gave me a piece of paper. I said, "What is this piece of paper? Is this what I won? I don't have my child." I knew that taking them to court would frighten them and, of course, it did frighten them. So Tony vanished. He was very strong, thinking that the capitalists, with their money and lawyers and detectives, were pursuing him. It made him stronger.

LENNON: We chased him all over the world. God knows where he went. So if you're reading this, Tony, let's grow up about it. It's gone. We don't want to chase you anymore, because we've done enough damage.

ONO: We also had private detectives chasing Kyoko, which I thought was a bad trip, too. One guy came to report, "It was great! We almost had them. We were just behind them in a car, but they sped up and got away." I went hysterical. "What do you mean you almost got them? We are talking about my child!"

LENNON: It was like we were after an escaped convict.

PLAYBOY: Were you so persistent because you felt you were better for Kyoko?

LENNON: Yoko got steamed into a guilt thing that if she wasn't attacking them with detectives and police and the FBI, then she wasn't a good mother looking for her baby. She kept saying, "Leave them alone, leave them alone," but they said you can't do that.

ONO: For me, it was like they just disappeared from my life. Part of me left with them.

PLAYBOY: How old is she now?

ONO: Seventeen, the same as John's son.

PLAYBOY: Perhaps when she gets older, she'll seek you out.

ONO: She is totally frightened. There was a time in Spain when a lawyer and John thought that we should kidnap her.

LENNON: [Sighing] I was just going to commit hara-kiri first.

ONO: And we did kidnap her and went to court. The court did a very sensible thing -- the judge took her into a room and asked her which one of us she wanted to go with. Of course, she said Tony. We had scared her to death. So now she must be afraid that if she comes to see me, she'll never see her father again.

LENNON: When she gets to be in her 20s, she'll understand that we were idiots and we know we were idiots. She might give us a chance.

ONO: I probably would have lost Kyoko even if it wasn't for John. If I had separated from Tony, there would have been some difficulty.

LENNON: I'll just half-kill myself.

ONO: [To John] Part of the reason things got so bad was because with Kyoko, it was you and Tony dealing. Men. With your son Julian, it was women -- there was more understanding between me and Cyn.

PLAYBOY: Can you explain that?

ONO: For example, there was a birthday party that Kyoko had and we were both invited, but John felt very uptight about it and he didn't go. He wouldn't deal with Tony. But we were both invited to Julian's party and we both went.

LENNON: Oh, God, it's all coming out.

ONO: Or like when I was invited to Tony's place alone, I couldn't go; but when John was invited to Cyn's, he did go.

LENNON: One rule for the men, one for the women.

ONO: So it was easier for Julian, because I was allowing it to happen.

LENNON: But I've said a million Hail Marys. What the hell else can I do?

PLAYBOY: Yoko, after this experience, how do you feel about leaving Sean's rearing to John?

ONO: I am very clear about my emotions in that area. I don't feel guilty. I am doing it in my own way. It may not be the same as other mothers, but I'm doing it the way I can do it. In general, mothers have a very strong resentment toward their children, even though there's this whole adulation about motherhood and how mothers really think about their children and how they really love them. I mean, they do, but it is not humanly possible to retain emotion that mothers are supposed to have within this society. Women are just too stretched out in different directions to retain that emotion. Too much is required of them. So I say to John----

LENNON: I am her favorite husband----

ONO: "I am carrying the baby nine months and that is enough, so you take care of it afterward." It did sound like a crude remark, but I really believe that children belong to the society. If a mother carries the child and a father raises it, the responsibility is shared.

PLAYBOY: Did you resent having to take so much responsibility, John?

LENNON: Well, sometimes, you know, she'd come home and say, "I'm tired." I'd say, only partly tongue in cheek, "What the fuck do you think I am? I'm 24 hours with the baby! Do you think that's easy?" I'd say, "You're going to take some more interest in the child." I don't care whether it's a father or a mother. When I'm going on about pimples and bones and which TV shows to let him watch, I would say, "Listen, this is important. I don't want to hear about your $20,000,000 deal tonight!" [To Yoko] I would like both parents to take care of the children, but how is a different matter.

ONO: Society should be more supportive and understanding.

LENNON: It's true. The saying "You've come a long way, baby" applies more to me than to her. As Harry Nilsson says, "Everything is the opposite of what it is, isn't it?" It's men who've come a long way from even contemplating the idea of equality. But although there is this thing called the women's movement, society just took a laxative and they've just farted. They haven't really had a good shit yet. The seed was planted sometime in the late Sixties, right? But the real changes are coming. I am the one who has come a long way. I was the pig. And it is a relief not to be a pig. The pressures of being a pig were enormous. I don't have any hankering to be looked upon as a sex object, a male, macho rock-'n'-roll singer. I got over that a long time ago. I'm not even interested in projecting that. So I like it to be known that, yes, I looked after the baby and I made bread and I was a househusband and I am proud of it. It's the wave of the future and I'm glad to be in on the forefront of that, too.

ONO: So maybe both of us learned a lot about how men and women suffer because of the social structure. And the only way to change it is to be aware of it. It sounds simple, but important things are simple.

PLAYBOY: John, does it take actually reversing roles with women to understand?

LENNON: It did for this man. But don't forget, I'm the one who benefited the most from doing it. Now I can step back and say Sean is going to be five years old and I was able to spend his first five years with him and I am very proud of that. And come to think of it, it looks like I'm going to be 40 and life begins at 40 -- so they promise. And I believe it, too. I feel fine and I'm very excited. It's like, you know, hitting 21, like, "Wow, what's going to happen next?" Only this time we're together.

ONO: If two are gathered together, there's nothing you can't do.

PLAYBOY: What does the title of your new album, "Double Fantasy," mean?

LENNON: It's a flower, a type of freesia, but what it means to us is that if two people picture the same image at the same time, that is the secret. You can be together but projecting two different images and either whoever's the stronger at the time will get his or her fantasy fulfilled or you will get nothing but mishmash.

PLAYBOY: You saw the news item that said you were putting your sex fantasies out as an album.

LENNON: Oh, yeah. That is like when we did the bed-in in Toronto in 1969. They all came charging through the door, thinking we were going to be screwing in bed. Of course, we were just sitting there with peace signs.

PLAYBOY: What was that famous bed-in all about?

LENNON: Our life is our art. That's what the bed-ins were. When we got married, we knew our honeymoon was going to be public, anyway, so we decided to use it to make a statement. We sat in bed and talked to reporters for seven days. It was hilarious. In effect, we were doing a commercial for peace on the front page of the papers instead of a commercial for war.

PLAYBOY: You stayed in bed and talked about peace?

LENNON: Yes. We answered questions. One guy kept going over the point about Hitler: "What do you do about Fascists? How can you have peace when you've got a Hitler?" Yoko said, "I would have gone to bed with him." She said she'd have needed only ten days with him. People loved that one.

ONO: I said it facetiously, of course. But the point is, you're not going to change the world by fighting. Maybe I was naive about the ten days with Hitler. After all, it took 13 years with John Lennon. [She giggles]

PLAYBOY: What were the reports about your making love in a bag?

ONO: We never made love in a bag. People probably imagined that we were making love. It was just, all of us are in a bag, you know. The point was the outline of the bag, you know, the movement of the bag, how much we see of a person, you know. But, inside, there might be a lot going on. Or maybe nothing's going on.

PLAYBOY: Briefly, what about the statement on the new album?

LENNON: Very briefly, it's about very ordinary things between two people. The lyrics are direct. Simple and straight. I went through my Dylanesque period a long time ago with songs like "I am the Walrus:" the trick of never saying what you mean but giving the impression of something more. Where more or less can be read into it. It's a good game.