The Stories Behind Every John Lennon Song 1970-1980

by Paul Du Noyer

"I like to write about me, because I know about me." -John Lennon

Idealist, joker, showman, activist, poet and musician. John Lennon influenced a generation with his songs. This is the only book to explore the stories and thinking behind every song he recorded after The Beatles' breakup in 1970 - from the idealism and inner doubt of Imagine to the reaffirming love songs of Double Fantasy. Once free of The Beatles, John's style became more confessional than ever. "Imagine," "Mind Games," "Instant Karma": Lennon approach each song as another installment of his childhood, the bitter legacy of the Beatles, his love for Yoko, as well as his infidelities and his insecurity. There are also the classic anthems of social protest, like "Give Peace a Chance," "Power to the People," and "Working Class Hero." Even his choice of covers like "Standy by Me" and "Be-Bop-A-Lula," tells us much about his musical roots. Finally there are John's accounts of his domestic contentment and optimism for the future.

Illustrated throughout, this is essential reading for everyone who has been moved by the lyrics of one of the icons of pop culture.

Paul Du Noyer was born in Liverpool and educated at the London School of Economics. He is a rock journalist in London, and has written and/or edited for NME, Q, Mojo and The Story of Rock 'n' Roll.

Excerpt

SHINING ON

The world knew him as a man of peace, but John Lennon was born in violence. And he died in violence, too. He came into the world on 9 October 1940, when Liverpool was being bombed to rubble by Hitler's air force. The Oxford Street Maternity Hospital stood on a hill above the city centre; below it were the docks that had made the seaport great, but were now earning it a terrible punishment. Liverpool was Pearl Harbour every night in those war years, and thousands perished in terrace slums or makeshift shelters. But Julia Lennon's war baby survived, and she took it home unharmed. All around them was the din of sirens and explosions.

The Lennons' house was small, in a working class street off Penny Lane; John's father, Freddie, was away at sea. Liverpool was where generations of new Americans took their leave of Europe, and its maritime links with New York stayed strong. Freddie Lennon was like many Liverpudlian men, who knew the bars of Brooklyn better than the palaces of London. "Cunyard Yanks" became a source of the US R&B records that made Liverpool a rock'n'roll town. Black American music found a ready market in this port, which had grown rich by selling the slaves of Africa to the masters of the New World. In a park near John's home stood a statue of Christopher Columbus, inscribed: "The discoverer of America was the maker of Liverpool."

John was of the usual local stock, not so much English as Welsh and Irish. The latter, especially, had dominated Liverpool since the mass migrations of the famine years. They gave the Lancashire town a hybrid accent all of its own, which John never lost. The Celtic stereotypes were always applied to Liverpool - violent and sentimental, lovers of music and words, witty and democratic. Far from breaking the mould, Lennon was that stereotype made flesh.

But his upbringing was traditionally British. His respectable Aunt Mimi looked after John from the age of five. With her husband George Smith she raised the boy in a neat, semi-detached house in Menlove Avenue, on Liverpool's outskirts. Post-war Britain was still subject to scarcity and rationing ("G is for orange," went John's poem Alphabet, "which we love to eat when we can get them"), but his circumstances were comfortable. He had a loving home, and was educated at Quarry Bank, one of the city's better state schools. His background was not as deprived as he sometimes implied.

Yet he could not forget that his natural parents had deserted him. Freddie left Julia, and Julia did not want her infant John. It was not until his teens that John would see his mother regularly, whereupon she was killed in a road accident. The tragedy seems to have compounded John's sense of isolation. As a child, he claims, he used to enter deep states of trance. He liked to paint and draw, and loved the surrealistic, "nonsense" styles of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear and Spike Milligan. But his quick mind made him a rebel rather than an academic achiever. To Liverpool suburbanites of Mimi's generation, the city accent meant a lack of breeding, while shaggy hair and scruffy clothes awoke pre-war memories of poverty. John made it his business to embrace all those things.

Rock'n'roll was his salvation, arriving like a cultural H-bomb in mid-Fifties Britain when John was 15. But his musical education began earlier. As Yoko wrote in the sleevenotes to Menlove Avenue, a compilation featuring some of John's Fifties favourites, "John's American rock roots. Elvis, Fats Domino and Phil Spector are evident in these tracks. But what I hear in John's voice are the other roots of the boy who grew up in Liverpool, listening to 'Greensleeves', BBC Radio and Tessie O'Shea." As well as the light classics and novelty songs of that pre-television era, John learned many of the folk songs still sung in Liverpool ('Maggie May' among them) and the hymns he was taught in Sunday school. Like his near neighbour Paul McCartney, Lennon's subconscious understanding of melody and harmony, if not of rhythm, was already being formed many years before his road-to-Damascus encounters with Bill Haley's 'Rock around the Clock' and Elvis Presley's 'Heartbreak Hotel'.

By the dawn of the 1960s, when John's old skiffle band the Quarry Men had evolved into Liverpool's top beat group, the Beatles, he'd absorbed rock'n'roll into his bloodstream. The town's cognoscenti were by this time devouring the sounds of Brill Building pop or rare imports of Tamla Motown soul. When Lennon and McCartney made their first, hesitant efforts to write songs instead of copying American originals, their imaginations were a ferment of influences. Country and western was the city's most popular live music, which is why the Beatles' George Harrison became a guitar picker instead of a blueswailer like Surrey boy Eric Clapton. Then there was anything from Broadway shows to football chants, to family memories of long-demolished music halls.

More than all of these, there was Lennon and McCartney's innate creative talent. They inspired each other, at first as friends and then as rivals. Their band, the Beatles, was simultaneously toughened and sensitized by countless shows in Hamburg, the Cavern and elsewhere. And in London they met George Martin, who was surely the most intuitive producer they could ever have worked with. Finally on their way, the Beatles were world-conquering and unstoppable.

All this was not enough for Lennon. Millions adored 'Please Please Me', 'She Loves You' and 'I Want To Hold Your Hand', but John soon tired of any formula, however magical. Hearing the songs of Bob Dylan, he was stung into competing as a poet. Turning inwards to his own state of turmoil, he yearned to test his powers of self-expression. He began lacing the Beatles' repertoire with songs of dark portent, such as 'I'm a Loser' and 'You've Got To Hide Your Love Away'. Attempting his most naked statement so far, he wrote a song that he simply called 'Help!' - but the conventions of Top 20 pop music ensured that nobody guessed he meant it.

As the Beatles gradually began to disappear behind moustaches and a sweet-scented, smoky veil, Lennon's lyrics moved towards more complex and original imagery. And yet paradoxically, there was greater self-revelation. 'Norwegian Wood', 'Tomorrow Never Knows', 'Strawberry Fields Forever' - while these songs were often suffused with gnomic mystery, the emotional presence of their creator remained unmistakable. He disclaimed the everyday, anecdotal songs that had become Paul's hallmark. "I like to write about me," he told Playboy magazine in 1980, "because I know me. I don't know anything about secretaries and postmen and meter maids."

His unthinking honesty almost killed him in 1966. A casual comment to a London newspaper - that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus - was shrugged off in Britain but summoned forth a torrent of death threats from America. "It put the fear of God into him," remembers Paul McCartney. "Boy, if there was one point in John's life when he was nervous. Try having the whole Bible Belt against you, it's not so funny." Coming through that, and having resolved the Beatles would not tour any more, John was ready for something else to happen in his life.

What happened was a woman named Yoko Ono. A Japanese artist, she arrived as if from nowhere and revolutionized John Lennon's life. "She came in through the bathroom window," he joked in 1969.

Pages

▼

Saturday, August 02, 2008

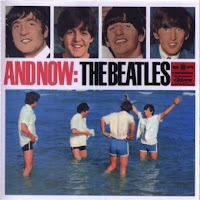

The Beatles - And Now: The Beatles (German Stereo LP - S*R International)

Label: Dr. Ebbetts, S&R 73 735

Label: Dr. Ebbetts, S&R 73 7351. She Loves You

2. Thank You Girl

3. From Me To You

4. I'll Get You

5. I Want To Hold Your Hand

6. Hold Me Tight

7. Can't Buy Me Love

8. You Can't Do That

9. Roll Over Beethoven

10. Til There Was You

11. Money (That's What I Want)

12. Please Mister Postman

Friday, August 01, 2008

The Beatles - The Beatles' Greatest (German Stereo LP - Odeon)

Label: Dr. Ebbetts, 1C 062-04 207

Label: Dr. Ebbetts, 1C 062-04 2071. I Want To Hold Your Hand

2. Twist And Shout

3. A Hard Day's Night

4. Eight Days A Week

5. I Should Have Known Better

6. Long Tall Sally

7. She Loves You

8. Please Mister Postman

9. I Feel Fine

10. Rock And Roll Music

11. Ticket To Ride

12. Please Please Me

13. It Won't Be Long

14. From Me To You

15. Can't Buy Me Love

16. All My Loving

Notes from Dr. Ebbetts

This title adds to the German canon. However, this title will raise some questions. Allow me to address what I believe will be the foremost points on everyone's mind. Indeed, this is the same track lineup and title as one already available in the catalogue - "The Beatles Greatest (Dutch stereo LP)." First, let me say that this is an entirely new transfer and, obviously, brand new artwork. Because this version sounds so much better than the Dutch LP, I have decided to use this audio as the official master for both. From now on, only the artwork variations will differentiate the two. The audio from the Dutch LP has been discontinued.

Behind the Spotlight

by Billy Shepherd and Johnny Dean

by Billy Shepherd and Johnny DeanAs January, 1965, came in, the Beatles were in their old familiar positions . . . top of the charts ("I Feel Fine") and the key talking point of the nation via their jam-packed "Christmas Show", which ran for three weeks at the Odeon Cinema, Hammersmith. Pictures of the lads, dressed in Eskimo gear for one sketch in which they met Abominable Snowman Jimmy Savile, flashed through the pages of even the most august newspapers in the land.

Sell Out

What a show that was at Hammersmith. It was a sell-out success right from the moment the box-office opened. It had some of the spirit of pantomime but any friend of the Beatles knew that they would never stick to anything remotely traditional.They threatened the safety of the theatre roof by causing ear-piercing cheers every time a Beatle arm or leg or head appeared in one of the sketches. And what's more the supporting bill was exceptionally strong . . . Freddie and the Dreamers, the Mike Cotton Sound, Sounds Incorporated, Brian Epstein's then new balladeer Mike Haslam, the Yardbirds and Elkie Brooks who was in such devastating form that if the Beatles hadn't been in top nick she would have landed the honours. Poor Elkie, who fast became a favourite with the Beatles, has, incidentally had a lot of throat trouble in recent months--otherwise we're sure she'd be right up there in the popularity polls.

The Beatles' act? Well, for collectors of Beatle lore, they did "I'm a Loser", which John tackled on a Bob Dylan kick; "Baby's In Black"; "Everybody's Tryin' To Be My Baby"; Ringo stepped vocally forward for "Honey Don't"; "I Feel Fine"; "She's A Woman"; "A Hard Day's Night"--and elsewhere in the show the inevitable "Twist and Shout" and "Long Tall Sally".

If the Beatles did well, the ticket touts did better. They were flogging ten shilling seats for four times that amount. Hammersmith has never since seen so much action over such a long time.

It was the Beatles' second dabble at a lengthy Christmas show. And as we now hear about the criticised "shortage" of Beatle live shows, we also think on what would have happened at Hammersmith had that show gone on, like a West End production, for as long as there was an audience willing to pay to go in. That Christmas show of 1964 would probably have run right through the year until Brian Epstein was forced to change the title to "Beatle Christmas Show 1965".

Supremacy

Actually though, the Beatle supremacy was better underlined in this way. During 1964, they'd been top of the charts for a total of fourteen weeks through the year. They couldn't help laughing at the fact that second best in this particular list was their old mate from the days of the Cavern, Cilla Black.Backstage at the Hammersmith Odeon was, as they say, somethin' else. Never, said the management, have there been so many potential gate-crashers. Old friends of the Beatles managed to get through . . . but the stage-door screening was done with the same ruthlessness as if organised by M.I.5. John established a new criterion for party acceptances: "How many people are going to be there that we haven't met before?" he asked. He was in very much a festive meeting-new-people mood.

We remember Ringo engulfed in an enormous woollen sweater with head- and arm-holes for two persons, and four giant initials "P, R, J, G" all over the massive chest. A fan sent it to the boys from Sweden. True to form, the boys wore it in an ad-libbed routine on stage that very night. Cynthia Lennon was in much demand, being pumped about how she's spent Christmas with John. "Very quietly," said she. "We just exchanged a few novelty presents and John had a good rest."

They're Unique

Brian Epstein was often there, still looking very pleased at the tremendous audience reaction to his "boys". A few journalists asked him, formally, how long he felt the Beatles could go on at this level of popularity. He shrugged, stretched his arms open wide, said: "They are unique. They have such distinctive personalities that I can't see any individual Beatle ever losing his appeal. But as a group? Well, I'd say at least two or three years right at the very top. After that, I'm convinced they each have magnificent careers in films."Towards the end of the Hammersmith show, the boys were out at parties most evenings after the programme. Often Brian Epstein drove them himself in his new Bentley Continental. Ringo was the keenest dancer at all parties, showing astonishing agility in the latest crazes, despite admitting himself to be "dead knocked out with tiredness".

But as January, 1965, came slowly to a halt, there was a lot of urgency for John and Paul, who had to complete the songs for the upcoming film. John actually afterwards nipped off for a ski-ing holiday in the Alps with Cynthia and recording manager George Martin. Paul stayed in London to complete HIS side of the song-writing. George also took a holiday, but Ringo decided that he'd spend a lot of time house-hunting. He said: "I've been spending a ruddy fortune on maintaining a flat in London and now I think I should find a proper pad of my own." Needless to say, estate agents fell over themselves once this little bit of information was printed in a London evening paper!

At this stage, John and George were the house-owners. Paul had bought property for his father and new stepmother, and furnished it too, but he also had thoughts of a complete new home for himself. A sartorial note from Paul at this time: "I've just bought a dead old-fashioned jacket, with wild lapels and it's black with very wide chalk pin-stripes." No need to stress, we suppose, that this sort of styling has been followed by umpteen people, including stars, throughout the land!

What everyone even remotely interested in the Beatles wanted to know was what plans they had for 1965 . . . and "remotely" interested included even the people who sold hot-dogs outside Beatle-concert theatres. And there were, even then, problems, for the boys had to go to America, had to make a film (possibly at this time even a third movie in the autumn) and they had to undertake a short European tour. They were genuinely perturbed that they might not get out round the country on a massive one-nighter scene, but as ever they had total confidence in Brian Epstein.

One surprise single out in Britain was "If I Fell" and "Tell Me Why" . . . a surprise because it comprised two L.P. tracks previously issued as a single only for overseas markets. But dealers had specially imported it for British fans . . . so EMI capitulated and it picked up substantial fan-following even among those who'd got it on the album.

But the boys enjoyed their short individual breaks from the business. We'll tell you why next month. . . .

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Way Beyond Compare: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy

by John C. Winn

The wait is finally over.

At last, there is one reference work describing every circulating recording from The Beatles' career.

Over 1,000 entries covering hundreds of hours of tape and film, from the Quarry Men's performance on the day John and Paul met in 1957 to Ringo's last stand with Phil Spector on April 1st, 1970.

No previous book has dared to brave the realm of Beatles interviews or explore the neglected areas of Beatles video and film work.

Newsreel footage, promo clips, TV performances, press conferences, home movies, radio interviews, and documentaries are all given complete in-depth coverage for the first time anywhere.

That's in addition to a wealth of studio outtakes, home demos, concerts, alternate mixes, BBC performances, and rehearsals. If it's out there, it's in here!

"['Way Beyond Compare'] has joined the ranks of prestige Beatles books (regrettably few in number) that I know I can rely upon when searching for an answer. It really is an impressive tome and I congratulate you on a marvellous job." - Mark Lewisohn, author of The Beatles Recording Sessions

"A massive - and tremendously useful - undertaking... earn[s] an instant place on the list of most essential Beatles references" - Beatlefan

"...Winn writes that he wanted to create 'the kind of [Beatles] book I've always wanted to see'. But it's a safe bet that it's a book other Beatles fans have always wanted to see as well." - Record Collector

"John Winn's 'Way Beyond Compare' contains volumes of Beatle information and insights not offered in any other publication. This, the definitive, most accurate, thorough, helpful, and authoritative document study of Beatle outtakes, live performances, broadcasts and compositional drafts, is also the ONLY credible source on spoken-word recordings such as press conferences, interviews, skits and unscripted banter. Winn's welcome ability to accurately date every aural fragment catalogued here--often correcting conventions that have been uncritically accepted for ages, along with his acute analytical savvy and his ears-wide-open expertise, result in a beautifully written study of every Beatle sound to ever reach the public. Winn's two-volume set is indispensible for any collector of Beatle recordings, and is highly recommended for anyone wishing to learn more about what the Beatles played, sang and said." - Walter Everett, author of The Beatles As Musicians

The wait is finally over.

At last, there is one reference work describing every circulating recording from The Beatles' career.

Over 1,000 entries covering hundreds of hours of tape and film, from the Quarry Men's performance on the day John and Paul met in 1957 to Ringo's last stand with Phil Spector on April 1st, 1970.

No previous book has dared to brave the realm of Beatles interviews or explore the neglected areas of Beatles video and film work.

Newsreel footage, promo clips, TV performances, press conferences, home movies, radio interviews, and documentaries are all given complete in-depth coverage for the first time anywhere.

That's in addition to a wealth of studio outtakes, home demos, concerts, alternate mixes, BBC performances, and rehearsals. If it's out there, it's in here!

"['Way Beyond Compare'] has joined the ranks of prestige Beatles books (regrettably few in number) that I know I can rely upon when searching for an answer. It really is an impressive tome and I congratulate you on a marvellous job." - Mark Lewisohn, author of The Beatles Recording Sessions

"A massive - and tremendously useful - undertaking... earn[s] an instant place on the list of most essential Beatles references" - Beatlefan

"...Winn writes that he wanted to create 'the kind of [Beatles] book I've always wanted to see'. But it's a safe bet that it's a book other Beatles fans have always wanted to see as well." - Record Collector

"John Winn's 'Way Beyond Compare' contains volumes of Beatle information and insights not offered in any other publication. This, the definitive, most accurate, thorough, helpful, and authoritative document study of Beatle outtakes, live performances, broadcasts and compositional drafts, is also the ONLY credible source on spoken-word recordings such as press conferences, interviews, skits and unscripted banter. Winn's welcome ability to accurately date every aural fragment catalogued here--often correcting conventions that have been uncritically accepted for ages, along with his acute analytical savvy and his ears-wide-open expertise, result in a beautifully written study of every Beatle sound to ever reach the public. Winn's two-volume set is indispensible for any collector of Beatle recordings, and is highly recommended for anyone wishing to learn more about what the Beatles played, sang and said." - Walter Everett, author of The Beatles As Musicians

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Those Were The Days: An Unofficial History Of The Beatles' Organization 1967-2001

by Stefan Granados

This is the first complete telling of the Apple story, culled from exclusive interviews with the recording artists, staff and business associates who helped make Apple a fascinating chapter in the history of both the Beatles and pop music in general.

Today, the Apple office is remembered as a place where almost anyone could come in off the street and meet one of the Beatles, get funding for an outlandish art project, or just drop in to the Apple Press Office for a drink and a quick smoke. For less well-intentioned visitors, Apple was where one could go to pinch and electric typewriter, a box of LPs, or quite literally the lead off the roof of the Apple building at 3 Saville Row. But Apple was also the company that the Beatles used to discover and develop many deserving artists, including such stars as Mary Hopkin, James Taylor, Bad Finger, Hot Chocolate, Billy Preston and Mercury-award winning classical composer, John Tavener. Even a teenage Richard Branson figures in the Apple story..

Those Were The Days: An Unofficial History Of The Beatles Apple Organization 1967-2001 details the colourful history of Apple, from its inception to its current incarnation as the sole protector of the Beatles legacy.

Stefan Granados has diligently been researching this project now for several years and the book also contains many very rare previously unseen photographs.

Excerpt

1967 - The Nems years

Life in post-war England was relatively simple back in 1962. For aspiring professional entertainers like The Beatles - a four-man rock and roll band from Liverpool - a career in music promised little more than weekly engagements at local dances and youth clubs, and if they were lucky, perhaps a chance to cut a record that might get one or two spins on Radio Luxembourg or the BBC. Of course, fate held something quite different in store for The Beatles. Six months after their debut single Love Me Do became a minor hit, The Beatles sparked off a tidal wave of fan hysteria the intensity of which had never before been seen in popular music. During the halcyon days of 1963 and 1964, Beatlemania swept unchecked across the world. Show business, popular music and the world itself were changed forever.

Guiding The Beatles throughout the turbulent Beatlemania era was their manager, Brian Epstein. From 1962 to 1967, The Beatles were managed exclusively by Epstein and his artist management firm, Nems Ltd - an organization that Epstein himself had set up shortly after meeting The Beatles in 1962. Coming from an affluent Liverpool family, the mild-mannered Epstein was quite unlike the typical "pop" managers of the era. Prior to becoming the group's manager, Epstein's music industry experience had been limited to running the record department of his parents' Liverpool department store. But given that he was one of the few people in Liverpool to have actually conducted business with the London-based record companies, Epstein's decision to venture into artist management was not as far-fetched as it might have seemed at the outset. The Beatles were certainly impressed with Epstein's modest music industry connections and with his genuine enthusiasm for the band, so they signed a five-year management contract with him in January 1962. From that point onwards, all of the money generated by The Beatles was funnelled directly through Nems. In exchange, the four Beatles were each given a salary and had their living expenses paid by the company.

Initially, Epstein's management duties focused on securing a record contract for the group, polishing their professional presentation and overseeing the group's live bookings. But once the full force of Beatlemania took hold in 1963, The Beatles became increasingly reliant on Epstein and Nems to take care of almost every aspect of their personal and professional lives.

Receiving a 25% share of The Beatles' gross income, Epstein was certainly very well compensated for his efforts. But Epstein served the band with a remarkable sense of care and devotion and it was obvious that he regarded The Beatles as much more than just a once-in-a-lifetime business opportunity. In the early days of Beatlemania, Epstein's name was synonymous with The Beatles. Due in large part to the remarkable success of the group, Epstein was able to build Nems into a high-powered management company that would become the dominant force behind the Liverpool music scene.

Having seen what Epstein had done for The Beatles, almost all of the performers in Liverpool rushed to align themselves with Nems. From 1963 onwards, Nems Enterprises managed the careers of artists such as Cilla Black, Gerry and The Pacemakers, The Fourmost and Billy J. Kramer, as well as several lesser-known Liverpool groups.

Under Epstein's skilful direction, Nems developed a diverse and initially highly successful client roster, but it was clear to all of the other Nems artists that The Beatles were Epstein's one true passion. Whether charged with finding a house for one of The Beatles, negotiating television appearances or quietly settling such personal matters as threatened paternity suits, Epstein handled his duties in an efficient, dignified manner and all four Beatles considered him to be not only a manager, but a friend. When it came to The Beatles, no matter was too trivial to be given Epstein's full attention.

In retrospect, Epstein's only real professional shortcoming was his marked lack of business acumen. Still, while much of The Beatles' success can, and should, be attributed to their immense talent, it was Epstein's music industry contacts and his careful handling of the group's image and presentation that transformed The Beatles from a rough, leather-clad rock and roll band from "up North" into a polished, international show business phenomenon.

Today, Epstein's significant contributions to launching The Beatles' career are often overshadowed by the embarrassingly poor business deals that he negotiated on behalf of the group. The original recording agreement Epstein signed with EMI in 1962 was a one-year contract that gave EMI the option of extending The Beatles' contract for three successive years. In return, the band would get one penny of recording royalties for each single sold and precious little more for each album sold in the UK. For any Beatles recordings licensed to record companies outside of the UK, the group would receive only half of the UK royalty rate. Epstein would somewhat rectify matters when it was time to renegotiate The Beatles' EMI contract in January 1967. In exchange for re-signing to EMI until 1976, The Beatles would receive 10% of the wholesale price of a British album and 17.5% of the wholesale price of each album sold in America.

In Epstein's defence, the deals he negotiated for the group were fairly common by music industry standards in 1962. He would fare far worse with the non-music deals that he set up for the group. Epstein's most celebrated fiasco was the 10% royalty rate he negotiated for the American rights to manufacture and sell such seemingly trivial Beatles merchandise as wigs, shampoo, trading cards and the countless other items that flooded into American discount stores during 1964 and 1965. When Epstein entered into these deals in 1964, the 30 year-old ex-furniture and record salesman from Liverpool was no match for the quick-talking New York City businessmen who appeared to be offering him thousands of dollars in exchange for the simple use of The Beatles' name on what he perceived to be insignificant teen-oriented products. Due to the limited scope of his business experience, Epstein practically gave away the rights to The Beatles' American merchandising - a move that would ultimately cost The Beatles millions of dollars of revenue.

To be fair to Epstein, few music industry professionals at that time - let alone a music industry novice like Epstein - ever imagined just how much money music merchandising could generate. To Epstein, any revenue from the sale of such ancillary "Beatles products" was just "found money" to supplement The Beatles' live and recording income.

Never considered to be a great negotiator, Epstein's true strengths were his well-developed organizational abilities, his unflinching honesty and his conservative, reliable stewardship of The Beatles' finances. With Epstein overseeing the group's affairs, the four Beatles enjoyed a relatively carefree existence when it came to financial matters. If they wanted any item - be it a car, a house, or new clothes - they simply charged it to Nems and the bill would be paid with no questions asked. With Nems so thoroughly involved with managing their finances, the four Beatles made very few personal investments during the peak years of Beatlemania. The investment activities of the individual Beatles were limited to Ringo Starr's interest in a high-end construction company and Paul McCartney's decision (unbeknownst to the other three Beatles) to buy additional shares in Northern Songs, the music publishing company that held the rights to The Beatles' songs. In general, The Beatles seemed content to simply let Nems take care of business.

In addition to the money earned from live performances and record and music publishing royalties, The Beatles had several other sources of revenue prior to 1967. Their most significant collective investment was Subafilms, the Nems-run film company that controlled the group's share of The Beatles' film projects, responsible for producing Beatles promotional films (in the days before video) for television.

As well as owning Subafilms, all four Beatles held shares in Northern Songs Music Publishing, the company that held the publishing rights to The Beatles' songs. Although Northern Songs founder Dick James retained a majority interest in the company, The Beatles and Nems each held significant portions of Northern Songs. In addition to their Northern Songs stock, Lennon and McCartney were also co-owners of a company formed on 4 February 1965 named Maclen Music Ltd. Theoretically, Maclen licensed the rights to publish Lennon and McCartney songs to Dick James' Northern Songs with Maclen collecting 50% of the publishing royalties due to Lennon and McCartney from Northern Songs. The remaining 50% of the publishing revenue went to Northern Songs.

Dick James had been unusually fair to The Beatles (by industry standards of the day) when he set up Northern Songs in February 1963. Recommended to Brian Epstein by Beatles producer George Martin, James had a tremendous amount of respect for The Beatles and their music. Though The Beatles were little more than a talented group with one minor hit (Love Me Do) to their credit when James first met them in early 1963, James, a failed pop singer and then struggling music publisher, knew that the songs of Lennon and McCartney had the potential to become major hits.

In exchange for the publishing rights to The Beatles' second single, Please Please Me, James used his music industry connections to secure The Beatles a coveted spot on the BBC television programme Thank Your Lucky Stars. Impressed by his ability to get The Beatles on television, Epstein decided that The Beatles would sign with Dick James Music.

In a highly unusual move in an era in which songwriters would often sign away their songwriting royalties for an advance of twenty pounds or less, James set up a subsidiary company, Northern Songs, for the sole purpose of publishing the songs of Lennon and McCartney. As part of the deal James offered the group, the two songwriting Beatles and Nems were given shares in Northern Songs that represented almost 50% of the company's worth. By 1967, Northern Songs had been re-structured and had gone public, so in addition to having received significant cash payments between 1964 and 1966 for a portion of their equity in the company, Lennon and McCartney each still owned roughly 15% of Northern Songs' stock. George Harrison and Ringo Starr owned 1.6 % of Northern Songs stock between them.

But outside of investments like Subafilms and Northern Songs, all four Beatles seemed to be perfectly willing to let their royalties pile up in their Nems account and draw a weekly wage. It would not be until the mid-sixties that The Beatles, George Harrison and Paul McCartney in particular, began taking an increased interest in the group's business affairs.

In the innocent era during which The Beatles had emerged, it was generally accepted that artists were responsible for creating the music and that professional managers took care of business. Out of all of the English groups who sold millions of records during the "British Invasion" only Dave Clark of the Dave Clark Five had the foresight, and skill, to take full control of his group's business affairs. (In addition to negotiating a royalty rate with EMI that far exceeded that of The Beatles, Clark retained the rights to all of his band's master tapes and music publishing. He would also later buy the rights to the celebrated British pop music television show Ready Steady Go, giving him exclusive rights to live TV performances by The Beatles and almost every other top band of the mid-sixties.)

Even when Harrison and McCartney started to take a greater interest in the group's financial affairs, there was actually very little that one or even two Beatles could do to influence matters. Since the earliest days of the group, the band made all of their decisions by consensus. Given the success of this democratic system, each of the four Beatles were somewhat reticent to appear too domineering in the eyes of the others. In the interest of preserving harmony within the group, it was often simply easier to let Epstein or another outsider take care of business matters.

Compared to many of their contemporaries, The Beatles were unusually democratic for a pop group. The way they conducted their business was largely governed by the strong personal ties between the four members of the band. Having been bound together through the non-stop recording and touring schedule that they maintained for close to five years, by 1967 The Beatles enjoyed a near family-like relationship and were quite accustomed to doing almost everything together.

Each Beatle explored individual pursuits after the group ceased touring in 1966. These included such non-Beatles projects as John Lennon's acting role in the film How I Won The War and Paul McCartney composing the music for the film The Family Way. However, these projects were not regarded as serious efforts to establish careers outside of the group and none of the side projects seemed to detract from the band's intense camaraderie. When the group settled back into Abbey Road Studios in late 1966 to begin work on "Sgt. Pepper" they were still an incredibly tight-knit unit. In early 1967, the group even looked into buying a Greek island where they could live and work together. They went as far as to visit Greece and select a remote Greek island to purchase before they characteristically lost interest and dropped the whole project.

Curiously, while each Beatle had at one time or another stated that The Beatles as a group would not go on for ever, none of them appeared to envisage the possibility that there could ever come a time when they would no longer be on speaking terms. It was in this spirit that they entered into their next venture, the jointly owned business that would become Apple.

In late 1966, The Beatles and their financial advisors had started to explore options for setting up a new Beatles corporation that would consolidate the groups' business affairs and enable them to lessen the impact of the notoriously harsh tax system that existed in Britain at that time. (When Apple was formed, the group's income was being taxed at a rate of around 90%.) Additionally, the band had been informed by its tax advisors that they would have to collectively pay three million pounds in tax unless they offset their tax liability by investing in a business. It is important to note that Apple was not set up to replace Epstein and Nems. It was created as a tax shelter to complement, rather than replace, the existing business structure.

The first step towards creating this new business structure was to form a new partnership called Beatles and Co. in April 1967. To all intents and purposes, Beatles and Co. was an updated version of The Beatles' original partnership, Beatles Ltd. Under the new arrangement, however, each Beatle would own 5% of Beatles and Co. and a new corporation owned collectively by the four Beatles (which would soon be known as Apple) would be given control of the remaining 80% of Beatles and Co. With the exception of individual songwriting royalties, which would still be paid directly to the writer or writers of a particular song, all of the money earned by The Beatles as a group would go directly to Beatles and Co. and would thus be taxed at a far lower corporate tax rate.

The Beatles appeared to be so anxious to begin reaping the tax rewards offered by this plan that they entered into their new partnership agreement having given little thought to the possible future implications of their actions. John Lennon - who was taking copious amounts of LSD throughout the period that Apple was being set up - would later claim that he was so high during this time of his life that he didn't remember signing any new partnership agreement at all.

Peter Brown, a fellow Liverpudlian who had worked for The Beatles and Nems since 1962, explains the origins of Apple: "When Apple was formed, which was before Brian died... it wasn't called Apple, but the structure of the buyout was there. The reason The Beatles sold 80% of themselves to this entity, which would become Apple, and to change Beatles Ltd. to Beatles and Co. was to save taxes. The reason that the 80% sale was triggered was because of the accumulated royalties at EMI that they were due to receive and the fact that if the royalties had been paid to them as individuals, it would have been taxed at 85% or something like that. So this structure was set up by Clive Epstein [Brian Epstein's brother] as a tax structure. At one point it was suggested that this be a real estate company: that was the original idea for lack of anything else. They couldn't figure out what to do with all this capital. All of this was set up while Brian was alive. After Brian died, my recollection is that they then decided to take this entity and create what they did, which was Apple."

It was hardly coincidental that the formation of Apple coincided with a period of marked turmoil within the Nems organization. Due in part to Epstein's personal problems that sprung from his increasingly complex gay lifestyle and escalating drug use, there were times when Epstein seemed to be losing control of Nems. To Epstein's dismay, by 1967 The Beatles had also become aware of how Nems' handling of the band's American merchandising had cost the group millions of dollars of income. The Beatles also resented the fact that many lesser groups had secured far more lucrative record contracts than Epstein had secured for The Beatles.

Yet despite their displeasure with the deals that Epstein had negotiated and the deteriorating situation at Nems, The Beatles never publicly announced any intention to leave Epstein when his management contract expired in August 1967. None of the band's associates from that time believe that they would have ever left Epstein and Nems. Rather than take out their financial frustrations directly on Epstein, the group seemed to simply want to preserve the considerable sums of money that they were earning.

The new corporation would be the first step in preserving some of their hard-earned income. By mid-1967, The Beatles had established a basic corporate structure and now needed to find a business in which to invest their capital if they were going to receive any tax benefit. Given that they were among the best-known, most-respected young multi-millionaires in the world, The Beatles felt the need to invest in a business that would simultaneously complement their image and provide a good measure of financial security.

Given such an ambiguous mandate, The Beatles were decidedly unsure about what form Apple should take. By mid-year, Apple had evolved into little more than a handful of sketchy ideas and what was essentially a holding company for The Beatles partnership. But as 1967 wore on and The Beatles moved into one of the most adventurous stages of their development (both personally and musically) the group began to envisage Apple as becoming something much more ambitious than a simple tax shelter.

A good deal of the energy and enthusiasm that fuelled Apple's early development was drawn directly from the flowering youth culture and the exciting art and music scenes that had enveloped London towards the end of 1966. By the summer of 1967 - the much heralded "Summer of Love" - London (along with San Francisco) found itself at the epicentre of a burgeoning youth movement.

As the warm summer weather and increasingly carefree social climate infused the youth of Britain with a wonderful sense of energy and optimism, the BBC and pirate radio stations made sure that the entire nation was awash with the remarkable sounds of The Beatles' "Sgt. Pepper" album and of new records by such colourfully named groups as The Pink Floyd and The Jimi Hendrix Experience. The Beatles were quite taken with swinging London and it was not unusual to find one or more Beatles checking out "happenings" or performances by one of the many new bands.

It was not only music that was capturing the imagination of England's youth and the interest of the world's media. In almost every corner of London, new boutiques, art galleries and specialist bookshops were springing up and the best and the brightest young minds in England were attempting to reshape a few select London neighbourhoods in their own image. Comprising the first generation of English youth who were too young to feel the full impact of the Second World War, these fashionable teenagers and twenty-somethings felt free to pursue their interest in music, art and leisure and they did so with great zest. The introduction of drugs to the scene only served to bolster the generally giddy spirit of the time.

Poised at the absolute centre of all this activity was Paul McCartney. With his upmarket St. Johns Wood home in London, a beautiful sophisticated actress girlfriend, stylish clothes and immense musical talent, McCartney was among the best-known exponents of swinging London.

While the other three Beatles languished in the outskirts of London with their wives and young children, McCartney would attend beat poetry readings, check out the new bands, go to the theatre, listen to avant-garde composers such as Karl Stockhausen and even make experimental films. McCartney was fully consumed by the wave of creativity that had swept over London and he genuinely felt that The Beatles could - and should - use their wealth and influence to help nurture this exciting new scene.

One of the early ideas for The Beatles' new corporation was to set up a chain of record shops across England, the idea being that The Beatles would be able to amass sizeable property holdings under the pretext of purchasing shop space. It was an interesting idea, but it never got beyond the initial planning stages. With little progress having been made on establishing some sort of property-driven company, The Beatles - at the urging of Paul McCartney - decided that their first commercial venture would be a music publishing company.

Given the low start-up costs and The Beatles' collective expertise in songwriting, establishing a music publishing company was certainly a logical option to pursue. As the driving force behind the formation of a "Beatles company" it was McCartney who finally came up with an ideal name for the company - "Apple". As long-serving Apple Managing Director Neil Aspinall recalled in an Apple press handout: "Paul came up with the idea of calling it Apple, which he got from René Magritte. I don't know if he was a Belgian or Dutch artist... he drew a lot of green apples or painted a lot of green apples [the painting in question was Magritte's Le Jeu de Mourre]. I know Paul bought some of his paintings in 1966 or early 1967. I think that's where Paul got the idea for the name from." Even though it was initially not clear what form Apple would ultimately take, when the "Sgt. Pepper" album was released in June 1967, The Beatles had already mysteriously thanked "The Apple" on the back cover of the album.

Whatever tentative plans The Beatles may have had for Apple that summer, however, were certainly altered when Brian Epstein was found dead in his London home on Sunday 27 August 1967. Only 32 years old at the time of his death, Epstein had apparently accidentally overdosed on prescription sleeping pills. The Beatles, who were all in Bangor, Wales attending a lecture on transcendental meditation, were naturally devastated by the news. When reached in Bangor, The Beatles appeared before the news cameras to offer a statement, looking shocked and confused. John Lennon would later admit that it was at that moment that he first felt that The Beatles were finished.

Epstein's death was a pivotal event in the development of Apple. Despite The Beatles' loyalty to Nems and the Epstein family, now that Brian Epstein was no longer running the company, it was soon apparent that The Beatles' relationship with Nems would change. In the weeks following Epstein's death, The Beatles appeared willing to remain with Nems, yet they also indicated that they were now looking to gain more direct control of their personal business.

One of the most contentious issues between The Beatles and Nems after Epstein died arose when they learned that a brash Australian named Robert Stigwood was angling to take control of Nems. It later transpired that Epstein - unbeknownst to The Beatles - had indeed made plans to sell Nems to Stigwood. Prior to Epstein's death, The Beatles had assumed that Stigwood was simply another Nems employee and they were most annoyed that Stigwood felt that he could simply pick up where Epstein left off as manager of The Beatles.

Epstein had made Stigwood co-managing director of Nems in January 1967, allegedly with the intention of later starting a new management company for The Beatles and Cilla Black, and then selling the remaining Nems assets to Stigwood. However, within months of Stigwood joining Nems, considerable tension had developed between Epstein and Stigwood. Although Stigwood was responsible for bringing the Bee Gees and Cream to Nems, Epstein and Stigwood apparently had very different opinions as to how Nems should be run. Epstein was reportedly very concerned by Stigwood's excessive spending and by the summer of 1967 he was said to be trying to find a way to ease Stigwood out of Nems.

The problem was that Epstein had extended an offer to Stigwood and Stigwood's business partner, David Shaw, which would allow them to purchase a controlling interest in Nems for £500,000. The standing offer was valid until September 1967, and when Epstein unexpectedly died in August, Stigwood and Shaw announced their intention to exercise their option. Stigwood's plans for acquiring Nems were thwarted only after The Beatles, who had previously been unaware of Epstein's plan to sell Nems to Stigwood, informed Stigwood that there was absolutely no way that they would accept him as their manager.

Stigwood, who had little interest in Nems if it did not include The Beatles, abandoned his plans to purchase the company. Instead, he left Nems altogether, taking with him the Bee Gees and Cream and starting his own company, RSO.

With Stigwood out of the picture, Brian Epstein's younger brother Clive assumed control of Nems. For several months after Epstein died, The Beatles' relationship with Nems changed very little. Despite Brian Epstein's death, Nems would continue to oversee The Beatles' day-to-day affairs. In fact, it seems that The Beatles even contemplated taking a more active role in Nems and using the company as an outlet for discovering and nurturing new artists, which is exactly what they eventually did with Apple.

Ringo Starr admitted in a 1970 interview with Melody Maker:

"We tried to form Apple with Clive Epstein but he wouldn't have it... he didn't believe in us I suppose... he didn't think we could do it. He thought we were four wild men and we were going to spend all his money and make him broke. But that was the original idea of Apple - to form it with Nems... we thought now Brian's gone, let's really amalgamate and get this thing going, let's make records and get people on our label and things like that. So we formed Apple and they formed Nems, which is doing exactly the same thing as we [Apple] are doing. It was a family tie and we thought it would be a good idea to keep it in, and then we saw how the land lay and we tried to get out."

Peter Brown, the Nems employee who inherited the lion's share of the responsibility for looking after The Beatles after Epstein's death, does not think that the idea of The Beatles using Nems to discover and develop talent was a likely proposition. "I don't remember that and I'm sure that if that was so I would remember because there wouldn't have been anything like that being discussed without me knowing," recalls Brown, adding, "It would have been so foreign to Clive Epstein that I don't think that it would have been workable."

Whatever the situation may have been, The Beatles appeared to be willing to stick with Nems for the time being. At the same time, they were also anxious to start handling some of their own business and creative affairs. Only weeks after Epstein's death, the first Apple project was already well under way. Apple's first venture would be the production of a new Beatles movie called Magical Mystery Tour which was filmed and edited in various English locations from September to November 1967. Cooked up by Paul McCartney on a long flight back from America, Magical Mystery Tour was intended to be a spontaneous, hip, art movie that would capture the free-spirited vibe of the summer of 1967.

Since Apple had yet to develop any formal staff structure, Beatles road manager Neil Aspinall and Paul McCartney assumed most of the responsibility for coordinating the various aspects of the film's production. The resulting chaos - which ranged from the "Magical Mystery Tour" bus and film crew venturing down small roads in rural England only to encounter a bridge that was too low for the bus to pass under, to not having enough hotel rooms for the entire cast - surely must have made The Beatles miss the brisk efficiency of the Nems organization.

For the first few months of Apple's existence, it did not even have an office - most Apple business was conducted from the Nems building. It was not until the autumn of 1967 that Apple finally opened a London office. Since The Beatles already owned a four-storey building at 94 Baker Street, that had been purchased as an investment

property by their accountants, they decided that Baker Street was as good a location as any for Apple. They set up an office for Apple Music Publishing in the Baker Street building in September.

Excited by the novelty of being businessmen and anticipating Apple to develop further business interests, The Beatles appointed their road manager, Neil Aspinall, to be Managing Director of the budding Apple organization. Aspinall recalled in an interview with Mojo, "A lot of people were nominated or put themselves forward to run it... but there didn't seem to be any unanimous choice. So I said to them, foolishly I guess, 'Look, I'll do it until you find somebody that you want to do it.'"

Fortunately for The Beatles, Aspinall was not a typical beat group road manager. He was generally qualified to do far more than book hotels, load vans and set up musical instruments on a stage. Prior to becoming a full-time Beatles employee in 1962, Aspinall had contemplated a business career and had been close to completing a correspondence degree in accounting before his work with The Beatles took him away from his studies. But it was Aspinall's loyalty to The Beatles, rather than his innate business sense, that made him the natural choice to be Managing Director of Apple. After Brian Epstein died in August 1967, Aspinall and fellow road manager Mal Evans were the only non-Beatles left in The Beatles' inner circle and the group placed a high premium on trust and loyalty. The individual Beatles had complete trust in Neil Aspinall and the surviving members continue to do so to this day.

Unlike Aspinall, loyal Beatles road manager Mal Evans would not fit as snugly into the Apple concept. Though he would ultimately be given a free hand to scout talent and dabble in record production for Apple, it was agreed that Evans would probably be best suited to remain as a road manager for The Beatles.

With Aspinall's time fully consumed by the combined tasks of setting up Apple Corps and looking after The Beatles, the responsibility of running Apple Music Publishing was given to Terry Doran, a fellow Liverpudlian and friend of the group who had been a business associate of Brian Epstein. Prior to being named head of Apple Music Publishing, the colourful Doran had run a car dealership that he co-owned with Epstein. Doran is the first to admit that his experience in auto sales was not particularly applicable to music publishing. However, to The Beatles of 1967, enthusiasm and a social familiarity were sometimes worth far more than practical experience in a given field. To assist Terry Doran at Apple Publishing, Carol Paddon and Dee Meehan were hired as secretaries and Apple's first three employees were charged with setting up an office at 94 Baker Street.

Doran may have had absolutely no experience in music publishing, but he seemed to make the transition we Publishing, Shotton was probably not the best person to be put in

charge of a new Apple business. Prior to coming to London to run the Apple Boutique, Shotton had been successfully running a supermarket that John Lennon had bought for him to manage in 1965. Although Shotton had no experience of running a clothing boutique, the fact that he had run some sort of store, combined with the fact that Lennon, Harrison and McCartney had known Shotton since they were teenagers, made the amiable Shotton the right person for the job as far as The Beatles were concerned.

The hiring of individuals like Terry Doran and Pete Shotton also illustrated how The Beatles hoped that the open-minded business structure at Apple would provide an opportunity for young, not necessarily traditional businessmen to distinguish themselves in the world of commerce. Still excited by the novelty of being businessmen, The Beatles wanted to give friends from the same working class Liverpool background as themselves a chance to show the world that business was not the exclusive domain of the upper class, private school educated section of British society.

With great fanfare, Apple announced to the press that the Apple Boutique would open for business in November 1967. Predictably, due to several unforeseen delays, it was not until the evening of 7 December 1967 that the Apple Boutique finally opened its doors. To celebrate, Apple staged a gala grand opening where George Harrison and John Lennon mingled with invited guests who were feted with apple juice and green Granny Smith apples.

The Apple Boutique officially opened for business the following morning and the general public seemed to be genuinely fascinated by The Beatles' new shop. Even in a relatively progressive city like London, never before had such a strange collection of merchandise been collected under one roof.

The shop's stock was largely made up of vivid psychedelic outfits and posters created by The Fool. The boutique was also intended to serve as a retail outlet for the gadgets created by Apple Electronics. These creations included a transistor radio that could be used to broadcast music directly from a record player and a small box with randomly blinking lights that was dubbed "The Nothing Box". Tellingly, by the time the boutique opened, the only contribution that Apple Electronics had made to the boutique was to install the lighting in the shop. Magic Alex had also promised The Beatles a giant artificial sun to illuminate the opening of the Apple Boutique, although he was apparently unable to create anything that resembled that description.

The Fool had first come to The Beatles' attention through the design work they had done for the Savile Theatre, a London performance venue under the wing of Brian Epstein. Greatly impressed with The Fool's sophisticated psychedelic style, The Beatles hired the group to work on a variety of projects, which included painting a piano and a gypsy caravan for John Lennon, decorating the interior of George Harrison's bungalow and creating the outfit that Ringo Starr wore in the Our World broadcast performance of All You Need Is Love.

When The Beatles decided to open the Apple Boutique, The Fool were naturally asked to become the shop's in-house designers. In addition to conjuring up an unusually garish line of clothes, they were given the task of decorating both the interior and the exterior of the boutique. With an unrestricted budget and a brief to make The Beatles' boutique stand out on the relatively staid street of shops and private homes, The Fool designed a massive three-story psychedelic mural to grace the side of the building.

The resulting mural - a brightly coloured Indian-styled goddess that took up the entire side of the building - was nothing if not striking. But while The Beatles were quite pleased with the painting, other businesses in the area were less-than-enamoured by The Fool's creation. Bowing to pressure from the local council and the surrounding business community, Apple was soon forced to paint the wall white with a simple "Apple" scripted in the middle.

But having to paint over of The Fool's mural was the least of Apple's problems. Despite the steady flow of curious tourists and students who made their way to the shop, the Apple Boutique made little money. It seems that in addition to having to contend with uninhibited staff helping themselves to cash from the till, the boutique's stock was not as enticing to the public as The Beatles had anticipated. Outfits like designer Harold Tillman's see-through chiffon tuxedo that had seemed very hip in the psychedelic summer of 1967 looked quite out of place on the cold streets of London during the winter of 1967-68, and, for the most part, remained unsold.

In his fascinating memoir The Love You Make, Peter Brown remembers the Apple Boutique as a very unusual place of business. "Customers seemed to be there only to shoplift or to stare at Jenny Boyd [George Harrison's sister-in-law] who was working there as a salesperson along with a self-styled mystic named Caleb. Caleb slept underneath a showcase on one of his many breaks. The store was also sometimes tended by a fat lady who dressed in authentic gypsy costumes."

Reflecting further, Peter Brown admits that, "The Apple Boutique was a bit of a rip off. It was a case of The Beatles trying to be too cool for their own good. It was a beautiful shop. The merchandise looked great. I don't think it was very good quality, but you weren't looking for something to last forever, you were looking to look great next Saturday. Looking back, I suppose it's no worse than the rag industry today, where designers do what they can to take the capital they are given and run with it. But The Fool were really pretty hypocritical. They were pretending to be these cool, lovely people when they were in fact a bit less than scrupulous in the way they did things. The Fool would totally run rings around poor Pete Shotton. There was always this problem of them saying, 'Don't say that to me because we're too cool for it,' and he would be confronted with this problem of trying to be a businessman while trying to be cool at the same time."

Brown also insists that, contrary to popular belief, The Beatles were quite aware that the Apple Boutique was rapidly getting out of control. In January 1968, Pete Shotton was replaced by a more experienced retailer named John Lyndon. Realizing what he was up against, Lyndon immediately instituted more responsible business practices for the shop and made a valiant attempt to reign in The Fool's excessive expenditure. Despite Lyndon's efforts, it was estimated that the shop went on to eventually lose close to $400,000. On top of the money that was lost at the shop, it is alleged that the Apple organization would also have to write-off the cost of a Jaguar sports car that Apple had purchased for Pete Shotton but which it had never reclaimed after Shotton left the company.

To complement the Apple Boutique, Apple Retail set up a second operation called Apple Tailoring (Civil and Theatrical) in a shop at 161 King's Road. Established on 2 February 1968 and officially opened on 23 May, the shop was a partnership with John Crittle, the highly respected designer, who was a Director of the enterprise along with Apple's Neil Aspinall and Apple accountant Stephen Maltz.

By the end of 1967 Apple had developed into an interesting little company. Given that The Beatles had started the year with only a vague concept for starting a business to minimize their tax exposure, the fact that they managed to set up two fully functioning companies by the end of the year suggested that they had big plans for Apple in 1968.

This is the first complete telling of the Apple story, culled from exclusive interviews with the recording artists, staff and business associates who helped make Apple a fascinating chapter in the history of both the Beatles and pop music in general.

Today, the Apple office is remembered as a place where almost anyone could come in off the street and meet one of the Beatles, get funding for an outlandish art project, or just drop in to the Apple Press Office for a drink and a quick smoke. For less well-intentioned visitors, Apple was where one could go to pinch and electric typewriter, a box of LPs, or quite literally the lead off the roof of the Apple building at 3 Saville Row. But Apple was also the company that the Beatles used to discover and develop many deserving artists, including such stars as Mary Hopkin, James Taylor, Bad Finger, Hot Chocolate, Billy Preston and Mercury-award winning classical composer, John Tavener. Even a teenage Richard Branson figures in the Apple story..

Those Were The Days: An Unofficial History Of The Beatles Apple Organization 1967-2001 details the colourful history of Apple, from its inception to its current incarnation as the sole protector of the Beatles legacy.

Stefan Granados has diligently been researching this project now for several years and the book also contains many very rare previously unseen photographs.

Excerpt

1967 - The Nems years

Life in post-war England was relatively simple back in 1962. For aspiring professional entertainers like The Beatles - a four-man rock and roll band from Liverpool - a career in music promised little more than weekly engagements at local dances and youth clubs, and if they were lucky, perhaps a chance to cut a record that might get one or two spins on Radio Luxembourg or the BBC. Of course, fate held something quite different in store for The Beatles. Six months after their debut single Love Me Do became a minor hit, The Beatles sparked off a tidal wave of fan hysteria the intensity of which had never before been seen in popular music. During the halcyon days of 1963 and 1964, Beatlemania swept unchecked across the world. Show business, popular music and the world itself were changed forever.

Guiding The Beatles throughout the turbulent Beatlemania era was their manager, Brian Epstein. From 1962 to 1967, The Beatles were managed exclusively by Epstein and his artist management firm, Nems Ltd - an organization that Epstein himself had set up shortly after meeting The Beatles in 1962. Coming from an affluent Liverpool family, the mild-mannered Epstein was quite unlike the typical "pop" managers of the era. Prior to becoming the group's manager, Epstein's music industry experience had been limited to running the record department of his parents' Liverpool department store. But given that he was one of the few people in Liverpool to have actually conducted business with the London-based record companies, Epstein's decision to venture into artist management was not as far-fetched as it might have seemed at the outset. The Beatles were certainly impressed with Epstein's modest music industry connections and with his genuine enthusiasm for the band, so they signed a five-year management contract with him in January 1962. From that point onwards, all of the money generated by The Beatles was funnelled directly through Nems. In exchange, the four Beatles were each given a salary and had their living expenses paid by the company.

Initially, Epstein's management duties focused on securing a record contract for the group, polishing their professional presentation and overseeing the group's live bookings. But once the full force of Beatlemania took hold in 1963, The Beatles became increasingly reliant on Epstein and Nems to take care of almost every aspect of their personal and professional lives.

Receiving a 25% share of The Beatles' gross income, Epstein was certainly very well compensated for his efforts. But Epstein served the band with a remarkable sense of care and devotion and it was obvious that he regarded The Beatles as much more than just a once-in-a-lifetime business opportunity. In the early days of Beatlemania, Epstein's name was synonymous with The Beatles. Due in large part to the remarkable success of the group, Epstein was able to build Nems into a high-powered management company that would become the dominant force behind the Liverpool music scene.

Having seen what Epstein had done for The Beatles, almost all of the performers in Liverpool rushed to align themselves with Nems. From 1963 onwards, Nems Enterprises managed the careers of artists such as Cilla Black, Gerry and The Pacemakers, The Fourmost and Billy J. Kramer, as well as several lesser-known Liverpool groups.

Under Epstein's skilful direction, Nems developed a diverse and initially highly successful client roster, but it was clear to all of the other Nems artists that The Beatles were Epstein's one true passion. Whether charged with finding a house for one of The Beatles, negotiating television appearances or quietly settling such personal matters as threatened paternity suits, Epstein handled his duties in an efficient, dignified manner and all four Beatles considered him to be not only a manager, but a friend. When it came to The Beatles, no matter was too trivial to be given Epstein's full attention.

In retrospect, Epstein's only real professional shortcoming was his marked lack of business acumen. Still, while much of The Beatles' success can, and should, be attributed to their immense talent, it was Epstein's music industry contacts and his careful handling of the group's image and presentation that transformed The Beatles from a rough, leather-clad rock and roll band from "up North" into a polished, international show business phenomenon.

Today, Epstein's significant contributions to launching The Beatles' career are often overshadowed by the embarrassingly poor business deals that he negotiated on behalf of the group. The original recording agreement Epstein signed with EMI in 1962 was a one-year contract that gave EMI the option of extending The Beatles' contract for three successive years. In return, the band would get one penny of recording royalties for each single sold and precious little more for each album sold in the UK. For any Beatles recordings licensed to record companies outside of the UK, the group would receive only half of the UK royalty rate. Epstein would somewhat rectify matters when it was time to renegotiate The Beatles' EMI contract in January 1967. In exchange for re-signing to EMI until 1976, The Beatles would receive 10% of the wholesale price of a British album and 17.5% of the wholesale price of each album sold in America.

In Epstein's defence, the deals he negotiated for the group were fairly common by music industry standards in 1962. He would fare far worse with the non-music deals that he set up for the group. Epstein's most celebrated fiasco was the 10% royalty rate he negotiated for the American rights to manufacture and sell such seemingly trivial Beatles merchandise as wigs, shampoo, trading cards and the countless other items that flooded into American discount stores during 1964 and 1965. When Epstein entered into these deals in 1964, the 30 year-old ex-furniture and record salesman from Liverpool was no match for the quick-talking New York City businessmen who appeared to be offering him thousands of dollars in exchange for the simple use of The Beatles' name on what he perceived to be insignificant teen-oriented products. Due to the limited scope of his business experience, Epstein practically gave away the rights to The Beatles' American merchandising - a move that would ultimately cost The Beatles millions of dollars of revenue.

To be fair to Epstein, few music industry professionals at that time - let alone a music industry novice like Epstein - ever imagined just how much money music merchandising could generate. To Epstein, any revenue from the sale of such ancillary "Beatles products" was just "found money" to supplement The Beatles' live and recording income.

Never considered to be a great negotiator, Epstein's true strengths were his well-developed organizational abilities, his unflinching honesty and his conservative, reliable stewardship of The Beatles' finances. With Epstein overseeing the group's affairs, the four Beatles enjoyed a relatively carefree existence when it came to financial matters. If they wanted any item - be it a car, a house, or new clothes - they simply charged it to Nems and the bill would be paid with no questions asked. With Nems so thoroughly involved with managing their finances, the four Beatles made very few personal investments during the peak years of Beatlemania. The investment activities of the individual Beatles were limited to Ringo Starr's interest in a high-end construction company and Paul McCartney's decision (unbeknownst to the other three Beatles) to buy additional shares in Northern Songs, the music publishing company that held the rights to The Beatles' songs. In general, The Beatles seemed content to simply let Nems take care of business.

In addition to the money earned from live performances and record and music publishing royalties, The Beatles had several other sources of revenue prior to 1967. Their most significant collective investment was Subafilms, the Nems-run film company that controlled the group's share of The Beatles' film projects, responsible for producing Beatles promotional films (in the days before video) for television.

As well as owning Subafilms, all four Beatles held shares in Northern Songs Music Publishing, the company that held the publishing rights to The Beatles' songs. Although Northern Songs founder Dick James retained a majority interest in the company, The Beatles and Nems each held significant portions of Northern Songs. In addition to their Northern Songs stock, Lennon and McCartney were also co-owners of a company formed on 4 February 1965 named Maclen Music Ltd. Theoretically, Maclen licensed the rights to publish Lennon and McCartney songs to Dick James' Northern Songs with Maclen collecting 50% of the publishing royalties due to Lennon and McCartney from Northern Songs. The remaining 50% of the publishing revenue went to Northern Songs.

Dick James had been unusually fair to The Beatles (by industry standards of the day) when he set up Northern Songs in February 1963. Recommended to Brian Epstein by Beatles producer George Martin, James had a tremendous amount of respect for The Beatles and their music. Though The Beatles were little more than a talented group with one minor hit (Love Me Do) to their credit when James first met them in early 1963, James, a failed pop singer and then struggling music publisher, knew that the songs of Lennon and McCartney had the potential to become major hits.

In exchange for the publishing rights to The Beatles' second single, Please Please Me, James used his music industry connections to secure The Beatles a coveted spot on the BBC television programme Thank Your Lucky Stars. Impressed by his ability to get The Beatles on television, Epstein decided that The Beatles would sign with Dick James Music.

In a highly unusual move in an era in which songwriters would often sign away their songwriting royalties for an advance of twenty pounds or less, James set up a subsidiary company, Northern Songs, for the sole purpose of publishing the songs of Lennon and McCartney. As part of the deal James offered the group, the two songwriting Beatles and Nems were given shares in Northern Songs that represented almost 50% of the company's worth. By 1967, Northern Songs had been re-structured and had gone public, so in addition to having received significant cash payments between 1964 and 1966 for a portion of their equity in the company, Lennon and McCartney each still owned roughly 15% of Northern Songs' stock. George Harrison and Ringo Starr owned 1.6 % of Northern Songs stock between them.

But outside of investments like Subafilms and Northern Songs, all four Beatles seemed to be perfectly willing to let their royalties pile up in their Nems account and draw a weekly wage. It would not be until the mid-sixties that The Beatles, George Harrison and Paul McCartney in particular, began taking an increased interest in the group's business affairs.

In the innocent era during which The Beatles had emerged, it was generally accepted that artists were responsible for creating the music and that professional managers took care of business. Out of all of the English groups who sold millions of records during the "British Invasion" only Dave Clark of the Dave Clark Five had the foresight, and skill, to take full control of his group's business affairs. (In addition to negotiating a royalty rate with EMI that far exceeded that of The Beatles, Clark retained the rights to all of his band's master tapes and music publishing. He would also later buy the rights to the celebrated British pop music television show Ready Steady Go, giving him exclusive rights to live TV performances by The Beatles and almost every other top band of the mid-sixties.)

Even when Harrison and McCartney started to take a greater interest in the group's financial affairs, there was actually very little that one or even two Beatles could do to influence matters. Since the earliest days of the group, the band made all of their decisions by consensus. Given the success of this democratic system, each of the four Beatles were somewhat reticent to appear too domineering in the eyes of the others. In the interest of preserving harmony within the group, it was often simply easier to let Epstein or another outsider take care of business matters.

Compared to many of their contemporaries, The Beatles were unusually democratic for a pop group. The way they conducted their business was largely governed by the strong personal ties between the four members of the band. Having been bound together through the non-stop recording and touring schedule that they maintained for close to five years, by 1967 The Beatles enjoyed a near family-like relationship and were quite accustomed to doing almost everything together.